Home Ecuador

One day we were walking on a track that became rockier and more narrow the further we went, until it would no longer accommodate the small pick-ups that were the most practical and common type of vehicle to own. The mountains were sectioned into amorphous communities, each one centered on one of the white-washed churches that dot the landscape. As we walked we entered one of these areas by the name of Bulcáy, wherein resided a number of craftspeople practicing the art of backstrap weaving. At first we noticed the bunches of yarn hanging from porch railings or on lines in the yards, their hues of indigo and magenta brilliant against the browns and grays of the country. Then we saw the men sitting on the ground in the shade of their homes, the tapestry stretched taut before them as they weaved the fine fabric that we had seen so often, for it is used to make the shawl that is a common piece of the daily apparel of the country woman in this part of Ecuador. The shawl is sometimes referred to as paño, but the term might be more specifically associated with the knotting that is used to finish the shawl. The beauty of the fabric, woven in the ikat style in traditional designs, is apparent as the women dress in their finery to bring their wares and do their shopping in Gualaceo on market day. Its utility and strength is demonstrated by the method in which the women transport large parcels or young children; they bind the child or basket against their back with the shawl wrapped around their shoulders and knotted against their chest.

The white cotton thread used in the weaving is most often purchased in the city: Cuenca, Azogues, or maybe Quito. The peculiarity of the Ecuadorian style of ikat is that the design is incorporated into the warp before the weaving even begins. They do this by binding the warp thread at preconceived intervals, often using the fibers of the penco cactus. The proper intervals are the weaver’s secret, and determine the design to be used. The bound thread is dipped into vats of dye of the desired color. The exposed areas take the dye while the thread beneath the binding remains white. These were the colorful bunches of thread that we saw drying in the breeze. It was our impression that the women usually did the dying and the setting-up of the warp, while the men performed the weaving.

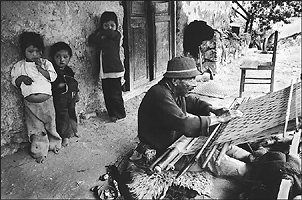

On our first walk to Bulcáy, we approached the home of a weaver named Miguel. He seemed as interested in us as we were in him, and invited us to sit with him in the shade. He was seated on the dirt floor with his legs braced on a log against the wall. One end of the loom was anchored to a frame on the wall. The other end was fixed with a strip of rawhide that looped around the small of his back and enabled him to use his body to control the tension of the loom. He seemed friendly enough as he grinned and peered at us from under his old hat. We were in an elementary stage of Spanish comprehension when we first met Miguel, and it didn’t help that his words were mangled by his ragged teeth before they even left his mouth, at which point they often became entangled in his grey stubble of beard. He was curious about us and life in the United States, and he liked to laugh. Our comprehension was always severely taxed when exposed to Ecuadorian jokes, but we had the distinct impression that Miguel’s jokes somehow concerned our sex lives.

Miguel’s wife, Selina, was a kind woman and somewhat easier to understand. She was fond of describing themselves as only “poor Christians”. She did the preliminary work for the weaving, setting up the warp in a small room off the porch, sitting on the floor with her glasses perched on her nose and held in place by a shoestring looped around the back of her head. There was one other room to their house, and a small building several yards away served as a kitchen and home to a small herd of guinea pigs that was both a source of income and nutrition.

As we sat with Miguel, we could look down on a shallow valley containing brown adobe-brick country homes, and watch the shadows of the clouds flowing over the fields of waving corn. It was a new and strange sight to us, while a very familiar one to seventy-eight year old Miguel. He had learned his craft as a young man before shoemaking had become such a quick and profitable source of income. The same was true of another old weaver whose son had taken up the trade of shoemaker. The shawls were worn primarily by the country women and, for the weaver, did not command a high price. Miguel could expect to earn about seventy sucs for his woven piece of cloth, and, if he were quick, he could finish weaving one in a day. The shoemaker could sell his shoes in the richer markets of Cuenca, Guayaquil, or Quito for 200 to 300 sucs per pair, depending on the style, and he could finish three to four pairs a day if he were industrious. For this reason, the craft of the backstrap weaver in this area of Ecuador belonged to the old men and women, and as they die, it will probably die with them. The younger men prefer the more affluent life of the shoemaker.

When the weaver has finished his work, he leaves a length of unwoven warp threads on either end of the piece to be used in the final step of producing a shawl, the paño. The weaver might sell his fabric directly to a woman who does the finishing, or to a middleman who buys fabrics to act as a supplier to people in the area. We visited the home of such a supplier in Bulcáy when we were seeking to purchase a sample of the weaving. We were shown into the sleeping and dressing quarters of the house where they had several piles of finished weavings for sale. The price varied, depending on the length of the fabric, and the coarseness of the weave. The initial asking price of a finely-woven piece about six feet long was 300 sucres, but after some bargaining, he let us have it for 250.

The actual finishing work on the warp threads is performed solely by women. We first noticed someone doing this work in the market square in Gualaceo. This woman tended a fruit stand most days, and she could be seen sitting on the ground in the shade of a canvas tarp behind her tables of oranges, avocadoes, papayas, and naranjillas. She was tall and gave the impression of thinness beneath her skirts and sweater and apron, a feat of legerdemain in a land of rice, yams, and potatoes. The features of her weathered brown face were strongly Indian, and she wore her black hair in braids beneath a white plastic hat. Before her stood a box over which was draped the fabric she was working on, held firmly in place by two large rounded stones from the river. Paño is the art of knot-tying, and this woman was busy knotting the loose end threads of the fabric into an intricate series of flowing designs and figures. As her hands and fingers moved, the tangled mass of threads were soothed into revealing a dove, a boy playing a flute, a monkey, a rose, or even the crest of the Ecuadorian nation, if the future owner was of a patriotic persuasion. The fingers absorbed the knowledge of the craft, and effortlessly tied and guaged the correct tension of each tiny knot. This final piece of work usually added about two feet of decoration to the length of the shawl, but could be as much as four feet, although I only saw paño of this dimension on shawls of older vintage. According to the skill or intent of the craftswoman, the paño might be exceedingly fine and intricate, or of simpler design. Paño is a time-consuming process, slower even than the actual weaving of the fabric, and can add greatly to the value of a shawl. A woman once offered to me an older shawl with a very long piece of paño, finely done. Her asking price was 2000 sucs, certainly worth it to a well-to-do American. Even in Ecuador, time is money, and the craft of paño has found its shortcuts. Sometimes the threads are knotted into a simple overall pattern, and pieces of embroidered cloth are cut and stitched over the knotting to finish the decoration. To our eyes, this method was much less attractive than the traditional forms of paño, however, it made the purchase of a shawl more affordable for many families.