Home Ecuador

We’d come to Azogues before on a market day. It was quite a bit busier than Gualaceo’s market. People in Gualaceo complained that the produce in their market was often that which hadn’t been sold in Azogues, and commanded a higher price besides, as if picked-over vegetables had greater value. If one made a lot of purchases while shopping in Azogues, there was usually someone there in the drayage business who could be hired to help move the load to house, bus, or truck. Sometimes the item would be carried by a man whose only tools were a rope and his back. He would squat down with his back to the cargo and loop his rope around it. Leaning forward, he’d pull the package onto his back, stand, and fasten the rope across his chest. Easiest transport in this fashion necessitated walking in a stooped position. Other men had two-wheeled wooden trucks like flat-bed wheelbarrows to take the weight of the merchandise. In Azogues, a city built on hills where the market took place on several levels, a third method of transport had evolved using four-wheeled, ground-hugging carts. On a central platform was a seat, a handbrake, and a cargo area to the rear. It could be steered with the driver’s feet placed on the pivotal front cross beam that held the wheels. Another set of wheels supported the rear end, and a rope for pulling was attached to the front. The carts would come flying downhill with their loads as ballast, swerving and weaving and braking through the foot-traffic. They were usually driven by young boys and accompanied by several more running nearby and shouting warnings to pedestrians at risk.

Waiting for our bus, we sat in the square and watched people walking around. The same people kept passing us over and over, walking around the square’s perimeter with their arms on each other’s shoulders, conferring and discussing in the spirit of good exercise. A squadron of boys selling ice cream was congregated on some steps nearby, making sorties through the parks and streets with their plastic buckets and plastic-lined baskets full of ice cream-on-a-stick. Their enthusiasm as salesmen waned with the day’s light, and they spent more and more time sitting on the steps. Or perhaps they were simply waiting for the easy sale – the bus stopped right in front of them.

We were happy to be on our way when our bus finally arrived. It was a bit ill-smelling on the inside, as if someone had hidden their used motion-sickness bag between the seats. The designer of the bus interior must have been intent on fitting the maximum number of seats while at the same time creating the impression of leisurely traveling. In this case, it made for a tortuous combination. The seats were spaced so close together that one’s knees were constantly in contact with the back of the seat in front. In addition, each seat was equipped with a reclining back which, when put to use, drastically reduced the space in the seat immediately behind. One was forced to recline in turn, partly to gain space, and partly in revenge. Consequently, when one reclined, all reclined. It becomes obvious that the seats at the very front of the bus become highly prized by long-legged Americans.

Darkness fell soon after our departure from Azogues. Still, it was possible to get a ghostly idea of the heights of the rugged mountain road, for a sliver of moon palely revealed canyon depths filled with mists and fog. When we arrived in Ambato, the jumping-off point for Baños, we took a taxi to the hotel. Our driver took us on an unannounced tour of the city before depositing us at the Hotel Asia, a couple of blocks from our point of departure. We were given a windowless room in the bowels of the hotel, where day was heralded not by the sunlight setting the walls aglow, but by a team of young athletes stomping and calling on the floor above.

We ate our breakfast in the hotel’s “penthouse” restaurant with a view of the city. It was a long room with tables end-to-end down the center. They were covered with a red cloth full of holes and a piece of old plastic on top for easy cleaning. It is the custom there, when the meal is done and the dishes removed, to wipe the remainder on to the seats and floor. Thus the floors are littered with bits of discarded food, and one must be sure to wipe the rice off one’s chair before sitting down. We ate a pleasant breakfast while looking over the rooftops to the mountains beyond.

Ambato is known as Ecuador’s “Garden City”. It is host to a festival each year called “Fiesta de Las Frutas y Flores”. We found a row of stalls selling fresh flowers: carnations, gladiolas, lilies, and others whose sweet fragrances were a wonderful respite from commoner city smells. There were many people in the streets, and the shops were full of the usual commodities. Sacks of grains, flour, and sugar stood in the doorways. We passed up and down rows of an indoor market overflowing with fruits and vegetables, even some artichokes, a rare sight. There was a river that flowed through town, a muddy-looking torrent, but still attracting women and children with piles of clothes to be washed. Back in the heart of the city we rested on a bench in a lovely park. An old Indian woman with a stick in her hand, muddy bare feet, and a soiled black shawl approached us with a cup in her hand. She had a wonderful and sad face, her life etched in deep and intricate wrinkles in her brown skin. I greedily thought to bribe her for a photograph, and placed a 5 suc note in her cup. Her face was transformed with an astonished look and she started to thank me profusely. Then she was obviously overpowered by her emotions and began to weep, took off her black felt cap and fell to her knees, saying something incomprehensible before regaining her feet and shuffling off. We were too amazed and embarrassed to do anything but stare. It was a shocking lesson on our own comparative riches, sometimes smugly held.

In Ambato we found the first Natural History Museum we’d seen in Ecuador. It was full of stuffed and bottled specimens of native wildlife. We felt that the composers of the groups must have had a sense of humor akin to ours. There were a number of domestic animals on display, cats and dogs; trees full of monkeys and sloths with an occasional plastic banana or marble included; an eagle in an alcove with a light fixture in its beak. Also preserved there were a quantity of nature’s less successful experiments. They reminded me of the “Two-Headed Baby” I saw once in a trailer parked on a street in downtown Los Angeles. Inside of bottles, floating in semi-clear preservatives, were a single-headed goat with two bodies, two-headed cats and cows, dogs and pigs without legs, “Siamese” pigs and guinea pigs, etc. They were the kinds of items reserved for carnival side shows in the United States. We saw only one carnival in Ecuador and it lacked a side show. In Ecuador, these curiosities became museum pieces.

The bus terminal in Ambato was a large field with the vans and buses parked side to side. As our taxi pulled up, several men called out destinations in the competition for passengers. We stated our goal of Salasaca, a community of weavers on the road to Baños, and we were escorted to a waiting van. The vehicle soon departed, but we drove slowly to the main road, soliciting passengers along the way. When we reached the highway, the driver put on his lead shoes, and we disembarked with some relief a short time later.

Salasaca appeared to be simply a few buildings along the road. One of these was the home of a cooperative show and sales room. The wool weavings were called tapices, and there were quite a few of them displayed on the walls and floor. In general, the tapices are somewhat lightweight, and better suited as wall hangings than use as rugs. They come in an array of colors, while any one of them was limited to two or three hues. There were various designs to choose from, but these seemed to be the most popular: birds, lizards, cats, anteaters, fish, figures of men and women, and abstracts. One man was present in the room, and we asked him where we might see some of the weaving done. He led us to a window, pulled back the shade and pointed out a house across a field. We went there and talked with several young men who wove tapices. It happened to be Saturday, and they were doing no more work that day. Their living and working quarters were combined in several rooms in a small adobe building. One of the rooms held two of the large, free-standing looms that they sit at while weaving. There was enough space left for a cane mat bed raised slightly off the ground. On the porch, in the shade of the roof, were two more looms. The spinning wheel that they used to transform tufts of the sheeps’ wool into yarn stood in the yard. To obtain the different shades, they dyed the yarn with dyes that could be purchased at the store.

As we talked, several people came and stood about. We assumed them to be family members. One of them was an ancient-looking lady dressed in black, as they all were, and wearing a broad, flat-brimmed hat. A young woman held a very small child in her arms. The women wore beaded necklaces. The men wore white pants under their black ponchos, and sporty-looking felt hats. These people, as others we met while traveling, were much friendlier if we were able to give them something in return for allowing us to visit their homes, and a symbol of our friendship. We’d brought a Polaroid camera and plenty of film for just such occasions. People in the country, particularly, appreciated these gifts, as photographs of their families were still somewhat hard to come by.

We wandered to a couple of other homes in the area. In one we were escorted to a corner of the room where the finished tapices were piled on the table and floor. The young occupants of the house were busy watching the television at the other end of the room. In another house, a small boy was working at the loom, making a smaller version of a design we’d seen elsewhere. Other persons in the house were very interested in what we might have to sell, eager to buy a sleeping bag or camera. Unfortunately, we weren’t ready to part with anything.

We returned to the dusty road and flagged down a bus that shortly deposited us in Baños. Immediately upon leaving the bus, we were accosted by a man hawking a residencial with “agua caliente” for what sounded indecently inexpensive. We didn’t trust him, and walked up the street to a small park where we eyed a residencial across the street, a likely prospect. The same determined man came up behind us, pointing out the fine qualities of his hotel, which happened to be the one we were looking at. We gave in, and received a very reasonably priced room above the street. We looked down on a small park, and a mountain wall a short distance across town looked down on us. It was a beautiful setting. Baños sits on a small level area butted against volcanic mountains whose thermal waters are legendary. The mountains on one side of town lead to the snow-capped cone of the volcano called Tungurahua. The other side of town is bordered by the spectacular gorge of the Rio Pastaza. Out of this depth climbs another set of mountains that marches into the distance. Banos suffers the certainty of occasional destruction by fiery outbursts from the nearby volcano.

A tourist town, Banos is filled with restaurants and hotels, residencials and pensions, and souvenir stands. One of the best-selling treats was taffy. We saw more people pulling taffy than doing anything else, except perhaps playing soccer. They take the sticky mixture hot from a pan on the stove, and slap it on a hook attached to a wall or post near the street. Then someone pulls it until it’s long enough to throw a loop around the hook, pulling and throwing in a vigorous effort to bring it to the proper consistency to break into pieces and wrap in brown paper. Up and down the street the candy is stacked in piles on tables in the doorways, the differently colored ends protruding from the paper to proclaim the various flavors.

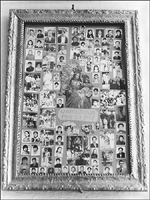

The hot mineral water, freshly percolated through stones heated by the molten rock deep below the earth, have a tradition of healing and life-saving properties that continues today, and enhances their “miraculous” reputation. The patroness of the waters is Nuestra Señora de Santa Agua, Our Lady of the Sacred Water. There is a very large church and an adjoining priestly compound, with a beautiful garden occupying the courtyard in between. There are a couple of cages in the garden, one containing birds, parrots and macaws, and the other housing several monkeys. Visitors enjoy teasing the animals, and sometimes being teased in return. A corridor runs along the wall of the church, with the garden on the other side. Walking here in the shade, one passes frames on the wall enclosing velvet-covered boards. Under the glass and pinned to the board are displayed miniature “milagros”, representations of human figures and parts of the body, done in silver. Further along is an alcove where pairs of crutches are mounted on the walls, and a portrait of Jesus acknowledges the miracle of those who shed their afflictions through their faith. There are letters of testament and displays of snapshots of some of those who have visited and have left a small donation in the box. At the end of the corridor is a small altar with candles set aflame by the faithful.

Entering the church, there is a small gift shop in a room to the left where one may purchase souvenir items of a religious nature: fingernail clippers with a small color portrait of Nuestra Señora on the handle, slide viewers, paintings, pictures, etc. Stepping through the doors into the nave, the space opens up and takes off. The heavy stone walls lift a vaulted ceiling into the semi-darkness above. Ahead wooden pews cling to the floor and draw their human occupants to them for comfort in their shared inconsequentiality. The huge and ornate altar glows in the distance at the far end of the room. The walls of this lavishly decorated church are mounted with large oil paintings illustrating some of the miraculous events attributed to Nuestra Señora. An accompanying text explains the circumstances. A number of these were concerned with duels with the raging Rio Pastaza that rumbled through its deep channel nearby. Whether the person fell from a bridge or was thrown from a boat or car, their survival against the cold, swiftly moving water was attributed to the blessed interference of La Señora. One of the stories, vividly portrayed on the wall, seemed to explain a tradition of the carnival festival. We were curious as to why people threw water during this celebration, but no one could give us any supposed reason. On the church wall was a story of the eruption of the volcano Tungurahua. On February 4, 1773, the mountain began spewing rocks and flames, and waves of molten stone. The people of Baños were threatened again with a fiery end, and invoked the name of Nuestra Señora, entreating her to deal with the mountain gone mad. While she was occupied there, they were busy throwing water on their homes and fields. The time of year of the action coincided with carnival activities. Well, it made a good story, but no one was impressed with our explanation.

There were several sets of baths to attend. Two were in town, and one was located in a small canyon a short distance from town. While the first pair simply resembled standard swimming pools, the last had a little more character, perhaps too much. The thermal pools were located beside a rivulet making its way down the shadowed canyon to become one with the Rio Pastaza beyond. The water looked like it had been leached of its healthful aspect, at least to our eyes. To others, the colored water probably represented the epitome of a therapeutic agent. The pools were located on several levels coming down the mountainside. On one level there were several pools with a bar and changing rooms, and suits for rent. On the next level were two more pools, one occupied by children splashing about on inner tubes, and the other by adults passively hanging around the edges. Nearby were several pipes imbedded in the mountain wall from which issued streams of water, and some people were soaping themselves and rinsing here. Other people were clambering up above the last pool and scraping the bright orange mud from the canyon wall and applying it to their bodies. There were even some hearty souls lowering their bodies into the shallow water of the canyon’s creek for a chilling respite. The water in the pools ranged from a greenish color to greenish-orange and orange. We took note of all this from behind a fence above the spectacle, not being able to wholeheartedly give ourselves to the suspicious-looking liquid. Instead, we attended one of the baths in town, located at the foot of a sheer mountain wall from which tumbled a waterfall. This waterfall was channeled in one direction through some pipes right next to the thermal pool, and in another direction into some clothes-washing troughs, and then through some toilets. This was no idle waterfall. The water coming from the pipes was quite cold, and we were instructed to rinse before entering the pool. Little did we know at the time that there were showers of hot thermal water available below. We were obliged water and it was not necessary to suffer the bite of this waterfall before enjoying the pleasure of the hot bath. There was also a cold water pool, and we alternated between the two in order to flog our central nervous system into an exceptional effort to cope, thereby ensuring increased longevity if not a heart attack. Then we went below to the showers where the hot waters gushed continually, and returned to our residencial to lie on our beds in a dreamy daze.

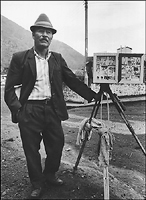

Besides taffy, the preparation and selling of sugar cane comprised another minor industry catering to the tourist trade. We were walking down the street into the teeth of a gusty wind when we came upon a gear-driven machine sitting by the road under the sign “Jugo de Caña”. Nearby in the shade of a row of cane sat a man. We indicated our desire for some juice, and he arose from his stool and approached the machine. He removed a cloth that covered the crushing gear and flipped a switch to set the wheels turning. Several strips of cane were fed into the apparatus. The cane pulp exited from the front and added itself to the pile already on the ground. The juiced coursed out the bottom, ran down a trough, and splashed into a wooden bucket. The man held a glass under a spigot at the bottom of the bucket and filled it with the fresh, sweet juice. Its popularity was easy to comprehend.

The cane could also be purchased raw from a lady in the street. She took her big machete in hand, hacked off a length of cane and, in a minimum of swift strokes, removed the outer husk and split the piece lengthwise into four sections. In this way, one had the pleasure of chewing the cane in addition to the delicious juice. The roads about town were everywhere littered with the white bits of masticated cane.

A row of booths stood on the edge of town near the rim of the Pastaza Gorge. Each small business was concerned with some food item, and several had cane crushers. We tried, one morning, to get some juice at one of the booths, but the gears of the machine jammed. While the operator overhauled it, we were attracted to a pole in front of the buildings. Atop the pole sat a small house on a platform, and the resident, a small monkey, sat on the porch, surveying the morning traffic. We didn’t want to get too close, because it looked as if it could stand a little excitement. The chain with which it was fastened to its home definitely limited its sphere of influence. It made its way playfully down the pole and onto the ground, casually interested in us. I put out my foot, and when the monkey jumped on it, I quickly withdrew it again. It was attracted to Peggy next who, unfortunately, was within striking distance. It didn’t wait for an invitation, but simply leaped onto her shirt front. She was startled and not too pleased. It wasn’t that the little beast was unfriendly, but rather a little too familiar at first acquaintance. I grabbed the chain and pulled it off, but it was ready for me. It ran up my arm and, from the vantage point of my shoulder, quickly began searching my hair, my shirt pockets, and grabbing my glasses. It knew there was little time. We were both moving pretty fast by then. I was trying to grab the chain again, but its feet on my head were distracting. It rapidly discovered that my pockets contained nothing of value to its knowledgeable fingers and, before I could get it off, it leaped back to the platform. It was a happy event for everyone in the audience, judging by the faces trying to laugh and chew sugar cane at the same time.

While wandering about Baños, we discovered someone in the orchid business. The yard of their house was full of these and other plants. They made periodic forays into the mountains to collect plants, many to be shipped to the United States. We thought it would be interesting to go along on one of the collecting expeditions, and got ourselves invited on one planned for a couple of days later. Even though they had to walk into the mountains, they said it was an “easy” journey. We arose early on the appointed morning, and went to the orchid collector’s house. They were preparing by sharpening several large machetes and knives on a flat rock in the yard. We waited for another of the party to arrive, and then were given knives before we set out on foot. We had to cross the Pastaza Gorge, for our destination was in the mountains on the other side of the river. There was a small footbridge high above the rushing waters that creaked and swayed in the wind, and brought to mind the paintings in the church and invocations of Nuestra Señora de la Agua Santa. When we reached the other side, the path immediately began winding steeply upward. The sun was still low in the sky, and the mists were moving out of the gorge and rising off the mountains into the air. Some bits of white vapor moved very rapidly upward in the warming air like ghosts suddenly realizing the dreaded sun was upon them. Though the air was cool where we walked, our exertion and the intermittent rays of the sun warmed us quickly. The dew lay thickly on the plants and earth, and soaked our shoes. Our company had split into two groups, one to gather tubers, the other the orchids from the trees. The first group had gone on ahead, while the second was slowing its pace in order not to leave the gringos in the dust. We were unused to the altitude and the strenuous exercise up the steep mountain path, and we urged the group to go ahead, and that we would catch up. The orchid collectors assumed their usual pace and rapidly disappeared into the heights. Peggy was afflicted with a headache that wouldn’t quit. She stopped for a rest, and I went on ahead to see if the men were working nearby. We were a good distance up the mountain by then. On a spur were some fields, homes, and a school, and an unusual sight: concrete wash basins and showers. The steep flanks of the mountains were spotted with areas under cultivation of corn, cabbage, potatoes, etc. The path had split several times, and it was unclear which way the men had gone. We made a slow, exhausted descent back to Baños and our beds, our orchid gathering finished before it had begun.

We had heard that there were cockfights in Baños and, being strangers to this activity, hoped we might have an opportunity to attend a match. The manager of our residencial happened to be a big fan, and clued us in on the time and location. We found the place, a small wooden building, and arrived a little early. Within the building was a small arena surrounded by a low wall, and set around the perimeter were some wooden bleachers about four tiers high. It was an intimate setting for the coming battles. There were a number of men already seated, or standing in the arena and talking quietly. Other men were arriving with their birds and putting them in wooden cages near the wall, or bringing them to the arena where the fans could look them over. All talk and speculation shifted to the cocks, who were examined and showed off and bragged about. The little building became livelier, and refreshments were being sold at the door. From the ceiling above the arena hung three bare bulbs, a scale with a cloth sling, a timer, and a piece of wood from which dangled several red rags and a bottle containing a clear liquid. As the beginning of the first match approached, the talking got louder and bets were placed while the steel spurs were fitted to the birds’ legs. When everyone was ready, the referee rang the bell, and the birds were thrown onto the dirt floor of the arena. The match started fast with the birds leaping at each other through the air, and sparring with their necks. The men stood in their seats, calling out to others across the arena, and waving their fingers in the air. The birds eventually tired, and used their necks more than their feet. The match was declared to have ended when one of the birds stood over the other’s head three times, each time lasting a certain number of seconds. We weren’t familiar with the rules. For us, the show was in the stands, and if we were better able to understand Spanish when spoken semi-hysterically, we probably would have more fully appreciated it. We didn’t enjoy seeing the birds maim each other, so we left after two matches. After each match, the sadness on the faces of some was matched by the joy on the faces of others as the money changed hands.

One day we got on a bus to follow the Rio Pastaza downsteam to the town of Puyo. We had just passed through a tunnel bored through some impassable mountain rock when we came to a line of cars, trucks, and buses parked along the road’s edge. A helicopter was just lifting off from where a car lay flattened several hundred feet into the gorge. We hoped our driver had taken fair warning. In several places, water running down the mountain created a waterfall over the road like a Disneyland ride. We arrived in Puyo in the middle of the morning, and the heat was already stifling. We were deposited in a gravel parking lot surrounded on three sides by shopkeepers’ wooden stalls. We had come to Puyo with the expectation of seeing exotic animals in the shops. But the shops were many and the same, clothing, hardware, and groceries, with a few restaurants, bars, and a bakery. We talked with a veterinarian who revealed that lately the government had been cracking down on the trafficking of wild animals. We found one shop selling authentic “Indian made” pottery, net baskets, arrows, and blow guns. After that, Puyo just seemed like a hot, dull town, and we didn’t waste any time returning to the beauty of Baños.

The following day we left Baños early in the morning on a van bound for Riobamba. It was a very pleasant ride through the mountains, for the air was brilliantly crisp, and the sharp rays of the sun revealed a glory in every direction. Much of our ride was along the flanks of Tungurahua, whose brown slopes and snow-covered summit stood unveiled by clouds. When we left the van in Riobamba, we hiked quite a distance through the streets looking for a hotel. We finally found them all clustered around the train station, along with the offices of the bus companies. We obtained a room with a great view of the railroad tracks.

As we walked about town we spotted several snow-covered peaks, but couldn’t tell which was our old friend Tungurahua, for they might also have been Chimborazo or Altar. We came across several small markets. There was an abundance of woven straps and belts for sale. In between a couple of stalls stood an old Indian man who seemed to have only one belt left to sell. It was nicely done in pleasant and rather unusual colors, but there were a couple of small flaws in it. He was asking seventy sucs and, in the spirit of Ecuador, I eventually bargained him down to a not-to-pleased sixty-five. However, when I brought out my money, I didn’t have any change, so he got his seventy anyway.

In the darkness surrounding the railroad tracks early the next morning we waited for our bus home. There was an old lady sitting near the bus stop with a pot of a hot, sweet, fruity-tasting tea perched on her small charcoal warmer. It could be had with aguardiente or without. Either way, it served to bolster the spirit for the ride. I took a seat in the first row, next to the window. Peggy sat on the outside and was treated to the cloddish antics of the buses’ conductor. He was forever leaning on her, sitting on her, or stepping on her feet. His face was swollen looking and slightly discolored, as if someone had spent a good portion of the night swatting flies on his nose. His thick, heavy lips kept his mouth hanging open. He was rather lazier than most men in his position, and often appeared to be walking in his sleep. The driver was plagued by passengers he would pick up along the roadside who only wanted to travel a short distance, and who usually felt that the fares he asked were excessive. It was often that he opened the door to let these persons out again. The extra passengers were probably simply extra money in the driver’s pocket, but he felt no responsibility to stop for every one, and there were many. The people holding large boxes or sacks had the least chance, as they’re the most trouble. We had to stop several times where the road had moved or disappeared into the yawning valley below, and a tractor or bulldozer would create a thoroughfare while we waited.

Our road passed several settlements of a distinctive-looking group of Indians, perhaps the “Quichos”. The women wrap themselves in a black dress down to their ankles, and wear a black shawl around their shoulders. They have a light-colored, round felt hat on their heads from under which sticks the thin black hair that reaches their shoulders. Sometimes their hair hangs down their back in a braid bound with a colorful piece of cloth. Some wore a woven belt around the waist, and a thick pile of beads around the neck to accompany the dangling earrings. The men usually wore shoes, a pair of pants that was often red, a round felt hat or one in a sportier style, and always a red poncho. The homes were built of adobe with thatched roofs and, sometimes, thatched walls.

We left the bus at the road that forked from the main road on its way to Gualaceo. We had to wait about an hour before a small pick-up truck loaded us into the back, along with a couple of other passengers. A large truck with a cargo of horses came up behind us and the impatient driver went around. When he passed he knicked our truck, but that didn’t stop him. However, it briefly stopped our driver who inspected the damage, and then took off in outraged pursuit. We passed dump trucks and buses, bouncing down the road with the dust in our hair and faces. Eventually we got behind the horse truck, our man weaving behind and honking furiously. When he saw his chance, he passed in a cloud of dust, and pulled up in the middle of the road to test his small vehicle’s facility as a road block. We removed ourselves from the auto. The driver of the large truck decided to give us a break, and stopped. The horses were all scared and kicking. Four passengers disembarked and began arguing with our man, who threatened a lawsuit unless they forked over two hundred sucs. After some more argument, sucs were exchanged, and hands shook all around. And so we returned to Gualaceo.