Home Ecuador

A small hardware store on a corner near the main square was selling tickets for the bus that paused nearby on its way to Sucúa, a town northeast of Gualaceo. Sucúa was located on the very edge of the land that continued east to be swallowed in the vast Amazon rain forest. We spent the first five hours of the trip on a bench directly before the windshield. After leaving town and crossing one of the covered wooden bridges over the Rio Gualaceo, the bus began climbing into the rolling mountains. Much of the way, the road had been carved out of the mountainside. The mountain climbed steeply away from us on one side, while on the other it fell into rocky depths where a feeble stream splashed among the boulders. On the slanted mountain wall across this chasm were the occasional adobe homes and precipitously situated cornfields of the mountain-dwelling natives. I recalled what a friend in Gualaceo had told me of these farmers. Not many of them owned the oxen teams that were needed to pull the wooden plow which was used to prepare the earth to receive the corn seed. These oxen were rented from wealthier farmers, and it was a skillful and tricky maneuver to get the fields plowed without the oxen tumbling down the slanting ground. If they did fall, the farmer automatically assumed a very large debt to the man who had provided the animals.

As we climbed higher, the country became more barren, and thinly populated. We eventually reached a plateau, known as the “páramo”, a desert region where a lack of water combined with the poor and rocky soil to make farming a hopeless endeavor. These windswept reaches were covered with scraggly low bush to complement the barren rocks posing nearby. A short time later, our road twisted among some foggy pinnacles that marked the summit and the pass over these mountains. The conductor made a collection among the passengers and, while the bus paused briefly, he jumped out the door and ran up the path to a small shrine built into the stone. He deposited the offering with, perhaps, a quick thanks to the Virgin for this safe and successful passing and a prayer for continued surveillance, and then he ran back to the bus.

While climbing, our loaded bus seldom exceeded the speed of 25 mph, but now that we were descending our speed remained the same due to the stony and tortured nature of the road. The vegetation was thicker here. There were many trees, and these were strangely shaped from the thick mosses that swelled the trunk and limbs, and balls of epiphytes that bunched in the branches. As we descended further, switchbacks took us through narrow canyons where there were many fuschias and small wildflowers among the grasses, and we began to see palms and tree ferns. Now an occasional house was noticed planted amidst the greenery. At one point, there was a gap in the road that the bus was unable to go around. We had been waiting only a short time when some men arrived and attempted to bridge the gap with some logs. The more prudent passengers disembarked before the driver made his bid over the ditch. As the front wheels passed over the beams, one of them broke, and the bus joltedly paused. At this point, we few daring voyagers still aboard left our seats behind for the security of firmly-packed earth. The next step was the summoning of a tractor to fill the gap. The bus backed up for a running start, and we were soon on our way again.

Our bus arrived in Sucúa in the dark of the early evening, approximately eight hours after leaving Gualaceo. We were apprehensive about finding lodging at night, due to previous difficulties finding unmarked inns in the dark. Our first stop was a residencial immediately above a pool hall and bar. We were given a room that smelled strongly of bug spray, but wehad foolishly prepaid so we felt obliged to spend the night. The only toilet was well-hidden, but the nose knows. It was locked, and better left so. The insecticide had little effect, except perhaps to make the mosquitoes more keenly appreciative of our finely-brewed foreign blood. Unbelievably, our room looked a little better in the light of the early morning sun. We checked out. After a good breakfast, we found a very pleasant hotel nearby for the rest of our stay. It was located across the street from the town square, a very nice park with some trees and many colorful flowers.

We had left the adobes of the mountains behind. All the building in Sucúa was done with the readily available wood. The streets were unpaved and dusty. We went for a walk to the west, down a road which quickly changed to a rocky path. We soon came to a bamboo bridge over a small stream. Crossing this rickety bridge, we climbed some earthen steps, and found ourselves in someone’s yard. The gray wooden house was nearby. A woman emerged, and invited us over to sit on the porch. It was already quite hot and humid. A couple of other ladies approached from the bridge with some gardening tools, and then the three of them left to work among the plants of the garden. We wandered beyond the house through the thick vegetation. The humming of insects set the hot air on edge. We were not encouraged to walk far because the trails were deeply rutted and very muddy, and we had no boots. Returning to town, we wandered through the unremarkable hardware and clothing shops until the heat forced us tiredly back to our room.

The midday sun had abated somewhat when we strolled down a road leaving town, this time to the east. We were hoping to encounter a river that flowed by in that direction. Many of the thatched-roofed houses were built on stilts, with plenty of open spaces in them to accommodate the circulation of air. As we walked we passed several people heading towards town with loads of firewood on their backs. One man was lucky enough to have a horse to carry the load. The road narrowed and led into somewhat open country with very tall grasses and palm trees. After several miles, the former road had become a path that climbed a short hill. From the top was a view of a level expanse of grasses, palms, and other trees that filled the distance to another set of hills. There was no sign of the river that we were seeking. A gentle breeze rustled the leaves while the insects chorused to one another. The barking dogs, or crowing of a rooster, or the clacking of an axe splitting wood signaled man’s presence, and here and there a thin column of smoke located a habitation in the midst of the greenery.

We had worked up a thirst on our walk, our canteen being one of those things we neglected to bring. On our way back to town, we were passing some houses when we heard a voice behind us calling “papayas!”. A woman was gesturing at us, and invited us to her house where she had a number of football-sized papayas for sale. Several barefoot children sat on the steps at the rear of the house, or stood and watched as we marveled at the huge fruit. We bought one for about 5 sucs and carried it back to our hotel.

The next morning we boarded a truck for an hour ride to Macas, the capital of the province of Morona-Santiago. Its unpaved streets made it a typically dusty town. The wooden buildings were complemented by the greenery that grew uncontrollably throughout the area. A backhoe was busily digging the ditches for a new potable water system, usually one of the first improvements to be made in a town with the money that flowed along with the oil of Ecuador’s newly developing energy industry. Walking the hilly streets of Macas in the heat, it was a welcome relief to come to a stand or store where a cooler of juice could be seen bubbling in its plastic case. The juice of the tamarind or naranjilla always tasted so good, although the water with which it was made was of dubious quality. Still, after the sticky sweetness of a juice or cola, we found ourselves wishing for a glass of pure water.

We climbed a hill hoping to catch a glimpse of the smoking volcanic cone of Sangay, but were defeated by clouds around the horizon. Instead we saw the Rio Upano coursing along its rocky bed, and decided to walk there. The rocks of the river basin had been rounded by centuries of tumbling in the quick-moving waters. These stones were being loaded into trucks and destined for roads or buildings. The rocks and sand made walking a very strenuous activity in the glaring sun. When we reached the river, we turned and walked upstream to where some people were working near a small shack and several parked trucks. A cable was stretched from bank to bank above the water. Dangling from the cable was a cart. It was being used to transport people and crates of small, orange naranjillas across the river. The naranjilla is related to the tomato and is unique to this part of the world. The pulp within the thin, but firm, outer shell is green, and tart to the taste. It is very popular for making juices. When fully loaded, the cart was given a starting push, and quickly coasted halfway across the river. Then the passengers would haul themselves by pulling on the cable for the remaining distance. The naranjillas were loaded on the truck for market.

Nearby, several men were busy bringing cattle across the river. The cart was too small to accommodate the animals. A line was sent to the other side and attached to a steer, which was encouraged to descend the bank and enter the river. As it swam, the current swept it downstream while two men on the near side hauled on the line and drew it across. While pulling, the men had to negotiate the rocks on the river bank in an effort to keep abreast of the steer, a tricky and strenuous exercise for all involved. The wet cattle were hobbled among the rocks before being taken away in one of the trucks.

We were unable to get a ride back to town, and by the time we had walked through the rocks and sand and heat, we were prepared to drool on the first juice stand we encountered. We wanted to see some more of Macas, but the heat had drained our energy reserves.

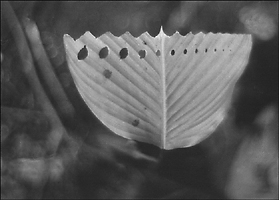

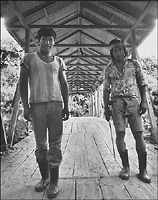

We slept well that night with the buzzing of mosquitoes kept at bay by the netting draped around our bed. The bus for Gualaceo didn’t leave until late in the afternoon, so we found a restaurant for some lunch. The lady who operated the business did some very nice beadwork that was similar to that done by some North American Indians. She told us about a river that flowed nearby, and the heat was our mandate to search for it. We followed the lady’s directions down a street that turned to a path that bordered Sucúa’s cemetery. The path took us through a little canyon full of palms and ferns with a small creek flowing along its bottom. Coming along the path towards us was a group of men and women, Jívaro Indians with long machetes in their hands. They were dark-skinned, with long, straight black hair, and dressed in light cotton clothing. They had been gathering plants nearby. As we continued, we could hear the sound of rushing water. We followed the muddy path down an embankment to reach the brown water of the swiftly moving river. It was crossed here by a covered bridge built of wood. From the other end walked two Indian men wearing high rubber boots and holding ominous-looking machetes. They were very friendly, pausing to say hello. Soon after we had parted, four Indian men came from behind us perched on mules which ably negotiated the uneven terrain. The Jívaros were strong and proud-looking people, outspoken and confident here where their lives had mingled for centuries with the other life of that land. They wondered if we were going to the village of Ascension? Perhaps some other time. Now we were headed for a good place to bath in the river, while several women washed clothes upstream.

Our ride back to Gualaceo was undertaken in a bus that greatly deserved the sobriquet “Bucket of Bolts”. The rattling racket over the tortuous road was head-splitting. The journey was characterized by the strong odor of aguardiente, which is handy for warding off the cold of a high Andes night, and by the retching of persons unaccustomed to motor travel. Our trusty, half-eaten papaya was wrapped in a plastic bag in my lap, fruit flies buzzing about, and its odor complementing the already nauseous atmosphere. Only the malfunctioning window prevented the papaya being tossed over a precipice in the night. It survived long enough to be transformed into papaya jam on our return.