|

|

Home Ecuador |

One day Noralma, our neighbor downstairs, invited Peggy to accompany her and her two children to share a meal of a peculiar delicacy called cáscaras. Cáscaras means “skins”, and, in this case, refers to the skin of pigs. One family in town prepared cáscaras regularly every Tuesday and Friday morning. We found this to mean that there was a good chance of encountering a meal at these times depending on the inclination of the chefs, proximity of holidays, availability of pigs, and so on. To an American, it is a refreshing and sometimes frustrating certainty of Ecuadorian life that very little is certain, or on schedule. Peggy was enthusiastic about cáscaras, and eager to inaugurate me in their consumption.

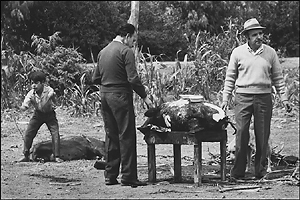

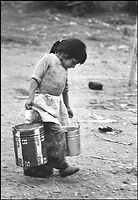

One gray Tuesday morning, with the clouds hugging the mountains and dampening us with an occasional misty rain, we set out through the dirt streets of Gualaceo to the home of the cáscaras makers. Their house was located near Gualaceo’s upper square where, on sunnier days, bunches of straw were fanned out in rows to dry. We were aware of the proximity of the feast by the scent of burning eucalyptus that drifted over the adobe-walled buildings. We passed through an open doorway and a short passage to emerge in an open courtyard. The near half of the yard was paved with concrete, while the far side was hard-packed dirt. A few tables and chairs painted in faded pastels were scattered about the patio. Lying on their sides in the dirt were three large, fire-blackened pigs, a light haze of smoke rising above them. A man moved nearby with a rake in his hands, clearing away the ashes that surrounded the pigs. The man’s wife, a large woman in skirt, sweater, checkered apron, and pigtails, watched over the scene from her position in the doorway of the cooking quarters which, along with the living quarters, formed the boundary on one side of the yard. Inside the kitchen was a dining table, a kerosene stove, an open cooking fire, and an assortment of pots, black with soot. Several barefoot children were standing about, and an army of disfigured dogs, new-born cats, and nervous chickens patrolled the scene. On the other side of the yard, opposite the kitchen, was a tree that supported a number of roosting hens in its gnarled branches. Nearby was a cement water trough. Stacked along the back wall were some accumulated odds-and-ends, a large quantity of red roofing tiles, coils of wire and rope, and a pile of eucalyptus branches which lent their aroma to the humid, smoke-laced air. The clouds thinned slightly and the sun glowed noticeably stronger, filling the yard with diffused light. This dreamy drama was unfolding to the accompaniment of a transistor radio that gave forth the guitar-accompanied harmonies of a series of pasillos, the tragi-romantic “musica nacional” of Ecuador. The man who was the owner of the house, and whom, when it came to preparing cáscaras, was the chief cook, exchanged his rake for a bunch of the eucalyptus. His wife came out of the kitchen carrying a hot brand from the fire and set the leaves aflame. The chef took his fiery wand and brushed it over the pigs, further searing the hair and skin. He continued the barbecue with successive bunches of branches, letting the fire linger over the entire length of the pig. We, the spectators and prospective customers, watched and waited with our noses twitching and our taste buds paralyzed in anticipation; waiting until that magic moment when the chef’s preparations were complete, when the hides had reached the pinnacle of blackened crispness. Now the chef stepped away and let an assistant, his son, rake away the debris. The man disappeared into the kitchen, and when he emerged again he was holding a long knife. He walked across the yard to a flat stone next to the trough and, splashing some water onto the stone, he whetted the blade to a fine edge. Returning to the pig, the man meticulously scraped away the layer of charcoal, occasionally drawing the knife between his fingers to clean it, and flinging the black residue to the ground. From underneath the burned crust emerged the golden-colored cáscara. During the pre-eating ceremonies, various inhabitants of Gualaceo had entered the yard and procured tin plates from the kitchen. Now they moved closer to the pig, irresistibly drawn by the golden glow. As a devotee, one had several sizes of portions to choose from, depending on one’s appetite, funds, and tolerance to the product. We were hungry, but leery of the beneficial effects of toasted pigskin. We asked for the twenty-suc size and handed the man our plate, which he place on the pig’s hindquarters while he sliced an appropriate amount of thin sheets of the cáscara. We carried our portion to a nearby table and used our fingers to consume it to the accompaniment of salt, a spicy salsa, colas, and moté, the Ecuadorian staple. The cáscaras, when prepared in such a way, were crispy with a thin layer of rich fat on one side, and an accent of smoky eucalyptus. They were habit-forming. As we ate, the chef’s wife would occasionally sojourn from her position in the kitchen doorway to serve a guest or, switch in hand, to reprimand an uncouth chicken which had leaped onto an empty table and was busily pecking at the moté. Several people came into the yard with an order “to-go”. They brought their own plate and, when they left, their pile of cáscaras was covered with a piece of brown paper. When we had finished, we wiped our hands on one of the towels that hung on a line stretched across the yard, and went to thank our host and hostess. They were curious to know how the gringos had enjoyed their meal, and we assured them that it had been a rare treat. We only regretted it later when our stomachs resorted to a tortuous system of knot-tying and we were obliged to stay within speedy access of a toilet. However, our taste buds were nothing but uplifted by the experience, and we were soon thinking again of cáscaras for breakfast. It was on the occasion of the second birthday of Carmina, Noralma’s daughter, that we were introduced to cáscaras prepared in a different fashion. We went with Noralma, her husband Román, her other daughter Carla, and little Carmina to Gualaceo’s central square where we boarded one of the transportivas that left regularly for Cuenca. We disembarked at a house that stood by the roadside amid the cornfields a short way outside of Gualaceo. Occupying the yard in front of the house was a low table and the omni-present volleyball net. On the table was a pig, deceased, laying on its side, and a group of people was gathered about it, stripping away and eating its skin. We walked over to the shade of the porch and seated ourselves on some benches. The building was locked, but we could see through the windows that the floor inside was large enough to be a meeting or dance hall. Along one side of this house were some smaller buildings that contained a kitchen and a store. On the other side of the house were three live pigs busily munching the refuse that was to be their last supper. It was a warm, sunny day, and we bought some colas to drink while we watched the volleyball game and the people coming and going. After a while, a couple of men walked over to the group of pigs, and dragged two of them squealingly away. This is a typical pig-human interchange. When the pigs were near the table, several more men helped to wrestle them onto their backs, with which the pigs were quite displeased. Perhaps they had heard of this ritual, some seemingly outrageous rumor. Their squeals were noticeably enraged, but these didn’t stop the knife being driven into their hearts, nor the blood that flowed with their lives into the dirt. They were immediately covered with a mound of dried corn husks and set ablaze in a pyre that consumed only the hair and freeloading parasites, and provided the heat to make the cáscaras palatable. In the meantime, the people at the table had finished their meal, and we had retained enough of our appetite to respond when the pig on the table was turned over to offer us a whole side of skin. We gathered around the animal and used it as both our table and our meal as we ate our fill of cáscaras with its usual condiments. We felt that this method of preparing cáscaras was definitely inferior to that used by the family in town. The cornhusks gave neither the golden color nor the pleasing crispness to the skin, and they lacked the distinctive and tasty accent of eucalyptus. While we were eating, more people arrived at the house, and some were engaged in a common form of celebration: drinking a local brand of sugar cane-derived liquor that was known as Zhumir. This elixir was consumed in various styles and disguises, sometimes mixed with 7-Up, at other times with a warm sugar syrup, or, the most popular way, straight up from the shot glass in a single wincing gulp. Nothing could really mask the distinctive taste of Zhumir, except more Zhumir. It was often taken after a meal to “settle” the stomach or, in what we felt to be a mistaken notion, to counter-act the harmful effects of pork. We were treated to some Zhumir after our round of cáscaras, and I’m hard-pressed to say what it was exactly that my stomach was protesting later in the afternoon. Even if I knew for sure, it wouldn’t have made much difference the next time either Zhumir or cáscaras were offered in my direction. |