Home Ecuador

When we arrived in Gualaceo, we decided to find a bakery in order to buy from the source and secure our freshly-baked supply. We were directed to the Moreno bakery, which we eventually located, though with some difficulty because they don’t advertise – everyone who needed to already knew where they were. Walking down the streets of Gualaceo, the buildings were located side-by-side with no space in between. A series of doors opened into shops, courtyards, and sitting rooms. There was no sign to mark the small grocery store that occupied the front room of the bakery. A small picket fence was placed across the doorway, keeping animals and small children either in or out. When we knocked, someone entered from a yard in the back, and let us in. We expressed our interest in seeing the bread baked, and were ushered through a very small courtyard, past the family’s kitchen, and to the bakery area. Rosa Moreno was the motivating force behind the operation, and she eyed us kindly and with great generosity. She was a large woman with dark hair pulled behind her head, always wearing an apron and with her sleeves rolled up.

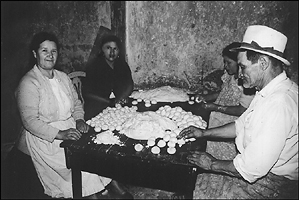

The first room she showed us was a small windowless one. A single bulb hung from the ceiling and radiated a dull glow over the proceedings. In this room, all the ingredients were mixed and the dough shaped. Along one wall were some wooden shelves, and nearby on the floor was a pile of tin baking sheets. On the other side of the room was a long wooden trough used to mix ingredients. Occupying the room from the center to the rear was a wooden table and the bakery workers were seated in chairs along either side. Rosa’s second-in-command was Christina, with freckled face and black hair in two braids over her shoulders. Her clothing revealed her identification with the Indians, the heavy red skirt with embroidery around the bottom edge, sweater, and checkered apron. Christina was more of an extrovert that Rosa, louder-talking, joking, and laughing. These two women comprised the backbone of the operation. There were a few other people who worked there off and on, plus members of the Moreno family.

After the ingredients were well-combined in the wooden trough, an armful of the dough was transferred to the table and thoroughly kneaded. Then the workers would begin shaping the bun. Different types of buns were made on different days and occasions. One of the most popular varieties for every-day use had a filling of manteca (pig fat) combined with the white, crumbly cheese of the area. Artificial coloring (we don’t know for certain that the coloring wasn’t some natural dye – we saw it once in powdered form at the pharmacy) was added to the filling mixture to make it yellow. This was supposed to be more pleasing to hungry eyes. When the bread baked, this yellow mixture would bubble out the top of each bun. Another variety of filling was a sweet one, brown and sugary, that made its appearance on special occasions and holidays.

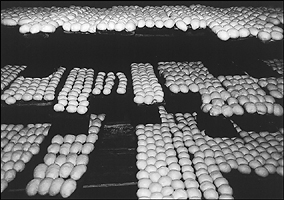

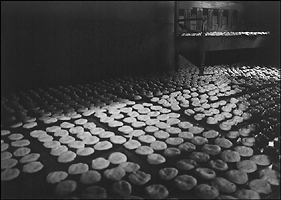

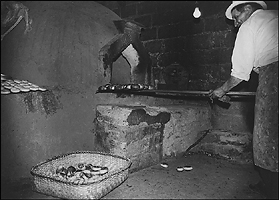

The bakers rolled pieces of dough under their hands to shape it into balls, and these were placed on the metal baking trays, about a dozen to a sheet. The trays of buns were set on wooden shelves to rise. If there was a large amount of baking to be done, which was often the case, the sheets of buns would spill over from the shelves into a nearby room where they covered the floor and bench. All this work of mixing and shaping the bread was done amid much conversation and joking among the bakers. One of the men, an old gentleman with white straw hat and bristly gray stubble on his face, liked to tell stories, and laugh and joke. He would often claim that Christina was his wife, which Christina always hotly and righteously denied, with some pushing and slapping in his direction.

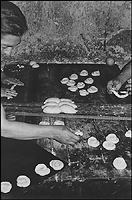

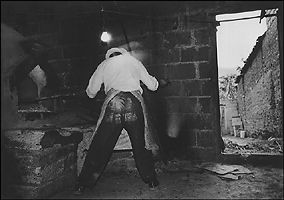

The most impressive piece of equipment was the oven. It was dome-shaped, about five feet high and eight feet in diameter, and set off the ground another three feet. Its thick walls were composed of brown clay. There was a single small trapezoidal opening in the front with a removable iron door. In order to heat it, the proper amount of wood was placed inside and kindled, and left to burn until nothing was left but the glowing red embers. When it was time to do the baking, these coals were either evenly distributed over the floor of the oven, or brushed to one side, depending on what was to be baked. The oven was loaded by one person using a long-handled paddle to place the tin sheets with the buns inside. There was an order to their placement, for the first ones in were the first ones out again. When the bread was done, the sheets were withdrawn in the same manner. The warm buns were tossed to some woven straw mats covering the floor in the corner of the room to cool. Customers took the freshly-baked buns away in large woven baskets, and they were sometimes peddled as far away as the town of Sigsig.

We spent many hours sitting on a bench near the oven, or in the dark mixing room. Our Spanish (they called it Castellano) was very poor at first, and our comprehension was severely taxed. A long comment by our hosts was often met with our “no comprendo”. But they were very patient, and generous, too. We were always given several buns when we arrived, and encouraged to take some home with us.

On our initial visit to the panadería, we were still thinking in terms of a loaf of bread. We had promised to return in the afternoon when we thought that they would be finished baking. When we did return later that day, we were shown upstairs to a large room that served the Morenos as their living room. There were windows looking out over the street, chairs arranged around the walls, and a phonograph and television. We were accompanied by Nelson, Rosa’s teenage son. We assumed that the bread wasn’t ready yet, and they wanted to entertain us during our wait. Actually the baking was mostly finished, but they thought that we would be more comfortable and better-amused upstairs. Nelson turned on the television which was showing some old American shows, one of which was the familiar skull-cracking and eye-gouging of “The Three Stooges”: dubbed in unfamiliar Spanish. The bread was soon done, and we finally realized the futility of seeking loaves in a country of buns. Freshly baked bread tastes wonderful no matter what its shape.

We had brought with us some “snakes”, a type of cheap firework commonly found at American Fourth of July celebrations. It is a small black cylinder that is lit with a match and begins to bubble and smoke with a spastic flame. Rising out of the center, twisting and turning, is a black “snake” of ash that grows until it breaks off or gets blown away, nearly weightless in the breeze. Nelson immediately set one ablaze on the wooden floor of the living room and was greatly entertained by the result, while we sat by horrified. The small round char mark on the floor commemorates our gift.

Rosa usually asked us if we were coming back “tomorrow”. If a week went by without our coming there, she was concerned for us. Whenever either of us came down with an ailment, the folks at the panadería always had suggestions for remedies, or gave us herbs, chamomile or lemon verbena, with which to make a soothing tea. Ironically, it was often a meal that we took at the bakery that required some sort of remedy, due mainly to our foreign digestive tracts.

Rosa was a devout Roman Catholic and was curious about our faith. She regularly went to the church for prayer, and wondered whether we, too, prayed? She was probably concerned for our souls after we tried to explain our somewhat atheistic, nature-worshipping beliefs.

We were often invited to return to the bakery for conversation and to watch old American-made television shows, like “Gunsmoke”. The Morenos and their friends were representative of the warmth and kindness of the people of Ecuador. Perhaps they had a soft spot in their hearts for Americans. It seemed that nearly everyone we met had a relative or a friend who had been, or was now, in the United States, mainly New York, to work for a time. These people were usually able to bring or send a comparatively large amount of money back home. This contributed to the myth that all Americans are rich. The myth has a basis in fact when one considers what a high proportion of the world’s raw materials are consumed in the United States, and when one compares the average American standard of living to that in other countries, particularly those of the “third world”. These considerations might bring one to the conclusion that, to a large extent, the edifice of wealth that constitutes life in the United States is built on a foundation of poverty in less-developed countries around the world.