Home Ecuador

Many of the buildings had small balconies facing the street, useful for a top-down participation in the street life while enjoying the comforts of the home. The balcony provided a platform from which to overhear the sadly-romantic tunes sung by a impromptu group of stumbling cantinistas; or to judge the innumerable processions marking religious and national holidays. During carnival festivities, the balcony was a strategic platform for launching water balloon attacks on the civilians below. Most buildings also had courtyards within, open to the air and light, and much family activity took place there. The climate does not require much adjustment for someone from California. Although lying just a few degrees south of the equator, Gualaceo’s height in the Andes (almost 8000’ elevation) tempers the heat and gives it a spring-like climate year-round. There is a rainy season which corresponds roughly to late summer-fall in the United States, but the year we were there, the rainfall was abnormally low. Agriculture was still very close to the life of most of the people, and we heard much talk of the lack of rain. Corn, a staple of the area, was spindly and the ears poor. The peach crop, in whose honor the town holds a peach festival each March, was said to be full of worms.

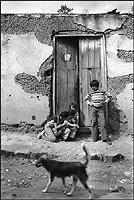

Two of the main streets of the town were paved with cobblestone for four or five blocks, and the rest were dirt. It was often windy, and the swirling dust provided a constant source of labor to cleanliness-minded housekeepers wielding brooms. Wetting down the street fronting one’s business with hose or bucket was a common practice.

The water service was irregular at best. A potable water system was being installed, but wasn’t to be operable for another year or two. We lived on the third and fourth floor of our building, one of the tallest in town. Since most water was used during daylight hours, the pressure was often too low for water to reach our home during the day. As a result, our toilet was often a hazardous area, particularly the day after eating something that turned the intestines inside-out. The water, when it was flowing, was brownish with silt, bits of plants, and microscopic animal life native to its source. We didn’t drink it, unless boiled or treated with iodine tablets. From the tap, anyway. We probably ended up consuming a lot of it in the form of tasty juices that we bought from vendors in the market, with sometimes unfortunate results. The natives didn’t care for it either, and this accounted for the large trade in sweet carbonated beverages. The bottles containing the soda were quite a valuable commodity in themselves. On a trip to the town of Vilcambamba, we payed an approximate $3 deposit on the bottle for a 12 cent soda. One advantage to this was we rarely saw broken bits of glass in the streets, and never a discarded bottle. When we first arrived, we purchased six bottles of soda from a nearby shop, including the usual bottle deposit, and would trade these in for refills periodically. Whenever the owner of the shop saw us, he politely inquired after our health before determining the condition of the bottles.

There were innumerable family-run shops in town. In the short block we lived, we counted three grocery shops, an auto and electrical parts store, and a cantina. The grocery shops were the most popular type of family business, and usually very small. They were not extremely well-stocked, and often seemed to have many of the same wares, but we could usually find something to satisfy our less exotic needs by shopping around. “Deli” foods were very hard to find except in the larger cities. Particular stores might specialize in a particular item, for instance, the family who had the homogenized milk concession, making daily trips to Cuenca for the plastic liter bags. Our downstairs neighbor bought raw milk from suppliers in the countryside, who would fill the pail she set out on the steps.

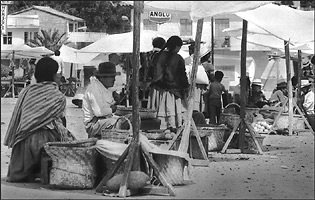

Sunday was Gualaceo’s main market day, and a number of usually non-existent stores, restaurants and cantinas opened their doors to welcome the influx of buyers and sellers. For most people, Sunday was a day of leisure and respite from the usual week’s work. It was a day to stock up for the coming week, do a little trading with the crowds, meet with friends, and take a picnic to the riverbank. The large concrete square next to the church, nearly empty the previous six days, became so crowded with stalls and people that it was difficult to walk.

The market was generally laid out in rows. Some sellers had tables and umbrellas while others sat on the ground in the sun or rain with their produce laid out before them. Specific locations in the market were reserved for a particular product. At one end of the square, Cańari Indians with their distinctive clothes and gray, rounded felt hats, arrived by bus & collectivo carrying burlap sacks overflowing with potatoes of every known size and color. Pork here, pork fat over there.

The women who sold the cooked pork were in attendance with their tables lined up in a row and wearing their billed caps or head-shades to ward off the bright Andes light. On each table was a wooden tray, and, perched upon the tray, the golden skin glowing in the sun, was a large roast pig, legs splayed to the sides, curled tail in the air, dead eyes staring straight ahead, and a grin on its lips. Roasted whole in this way, the meat was incredibly rich and flavorful. The seller was glad to give a sample, still warm from the fires. For a pound to-go, the woman would reach inside the carcass with a greasy hand and pull out a fistful of meat which she placed on a piece of brown paper on her balance scale. She would reach in again and break off some of the fat-encrusted, crispy golden skin and add this to the scale until it balanced with the rock weight on the other pan. She put it all in a bag and, if desired, a bit of marinated lettuce and vegetables. The ladies also sold for on-property consumption - plates of pork, along wit,some salad - and one could eat this at the tables behind them in the shade of a tarp or umbrella. There was a friendly competition between the ladies for customers. One lady whom we bought meat from several times used to attract our attention by hitting us from a distance with bits of thrown onion or carrot. A good shot, and not very subtle. Although many residents in town agreed that pork was bad for the health, there was no denying the pleasure to the tongue from eating it.

The beef, on the other hand, needed a lot of work to be made palatable. The sides of beef were hung from the market stalls with the sellers hiding behind them. In back of the stall was a chopping block consisting of a tree stump, where a man with an axe broke up the bones. People who sold beef usually owned several very large dogs. The choice was slim among the beef salespeople, and we usually bought our supply from a large, sullen-looking lady. We always asked for “puro”, meaning no bones, and she sold it to us, though she didn’t look happy about it. Later, we discovered from our neighbor that if she ordered a certain amount puro, she was forced to purchase an equal amount of bones. The beef was always very tough. We found it necessary to pound it to shreds with a stone from the river in order to render it chewable. We were driven to the extreme of buying a food grinder and making hamburgers and meatballs. However, the meat was so lean that these weren’t particularly tasty. Our friend Leonardo and his wife Claudia came over for hamburgers one night. We thought we’d present them with authentic American cooking. Mayonnaise also had to be prepared, as it wasn’t readily available in town. Leonardo and Claudia ate their buns piled high with mayonnaise, with the meat on the side.

On another side of the square, laid out on burlap sacks, were stacks of oranges or grapefruits, and nearby were tables of salt, sugar, and grains; and mounds of dark and light roasted ground coffee. Displays of multi-colored corn, red, yellow & white. Blocks of cane sugar, coconut, pineapples. Hard cakes of unsweetened chocolate in baskets. Eight foot long stalks of sugar cane stood in another vendor’s space. Young chickens, continually trying to escape from box or basket, were traddownace near the potatoes. There was a vast amount of produce available that changed as the seasons progressed. Eggs, expensive compared to prices in the United States, could sometimes be bought less dearly off a pick-up truck that rolled up with the market crowds and parked on the street bordering the square, flats full of eggs stacked in the back. Ground coffee Ecuadorian-style was available in pound quantities to single cup servings individually wrapped in brown paper. The coffee was ground extremely fine for use in cloth filtering bags. Hot water was poured over the grounds and thedark brown extract it yielded was called “tinto”. When the tinto was added to a cup of hot water, as was the custom, it resembled a cup of very weak instant coffee, barely tolerable by us confirmed espresso drinkers. However, they didn’t drink it in such an anemic state. They added milk and a generous amount of sugar. This coffee was ground so fine it plugged up our little espresso maker, and our caffeine addiction drove us to search out the only place we could find coffee of a usable grind: a clothing shop in Cuenca that happened to have a coffee grinding machine.

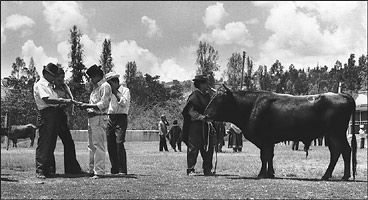

There were two other market locations in Gualaceo. One of them was a dirt square that, on most days, was covered with fans of straw drying in the sun preparatory to being sold or consigned to the people who weave the white “panama” hats. On Sundays the square was populated by the vendors of pots and pans and kitchen gadgets, clothes, boots and shoes, school supplies, lengths of woven rope, hand-woven textiles, and odds-and-ends of general interest. The other focal point of trade was located on the edge of town in a field normally reserved for soccer and volleyball. This was the livestock market, and on any Sunday morning the grassy field was crowded with bulls and cows, sheep, and the ever-popular pigs always in search of an appropriate hole of oozing mud. Professional buyers came into town with their brightly-painted trucks and bargained with the people who have brought their stock in from the country.The pig market is somewhat more locally oriented with locals stocking up on piglets to replace the pigs consumed during the week. The hum and bustle of market day business was continually punctuated by the distressed calling of recalcitrant pigs being pushed, pulled along the path to their destiny.

The holiday spirit and appetite of the market crowd are catered to by a row of stalls serving foods cooked on-the-spot in large pots over grills heated by glowing coals. Meals were most often served at a cloth and plastic covered table in the shade of a tarp. The first course was usually a soup, which was nearly always very good. Next came a plate of rice and beans, or potatoes topped with a small piece of beef, and a small salad alongside. A bowl of hot salsa was available on the table. The universal accompaniment to an Ecuadorian meal was a small plate of móte, a white, large-kernelled corn stripped from the cob and thoroughly boiled.

There were several juice vendors nearby. One juice that was particularly tasty was the coconut milk. Just before being served the juice was whipped to a froth in a blender along with bits of coconut meat. Weaving among the crowd in the hot sun are young boys and men with palettes of ice cream cones clutched in their hand, artists of the quick sell. Also available in a cone was a confection of whipped egg whites called rompope. This item was somewhat suspect to us, having been convinced back in the United States that it was an intestinal hardship, if not downright unhealthy, to consume raw egg whites. Our neighbor downstairs, Noralma, would occasionally whip up a batch of rompope as a special evening treat and send some up to us in a glass. It tasted good, and we ate it, but we came to associate it, rightly or wrongly, with what we called the “infamous egg burps”. These were a sulphurous belching in league with intestinal discomfort which could last a couple of days.

The main street connecting the two squares was lined with vendors sitting on the curbs and selling knick-knacks, household goods, and slabs of dark unsweetened chocolate. On one Sunday we met a woman with a basket out of which reached a bear’s paw. Inside the basket were deer’s hooves and vials of bear fat and animal unguents offered as treatment for various aches and pains.

As the day lengthened, the crowds thinned, and the dinner hour approached, there were some new items to be had in the marketplace. Some women brought out their charcoal grills, roasting sticks, and small pails that contained the skinned and well-marinated “cuis”, or guinea pigs. They skewered the animals and settled down before the coals to put a golden glow to the white bodies, while potential customers with a yearning for the delicacy inspected available specimens and negotiated with the owners. When a bargain was struck and the meal was roasted to perfection, the hungry customer rushed off to enjoy his meal, breaking off the bony feet and crunching them satisfyingly. Occasionally one of the woman would be roasting a chicken, but this was unusual. Some women were deep-frying epańadas, a donut-like treat dipped in sugar. Other women offered a product called tortillas, a fried patty of mashed corn kernels and anise seed, sometimes with a bit of cheese inside. It was all delicious. By the time everyone had gone home, all that was left in the square was a scattering of paper bits and vegetable debris, and an occasional scrounging rat. Early the next morning, several men with brooms of knotted branches had swept it spotless again.

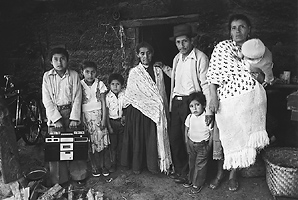

A couple of “cottage” industries dominated the economic life of Gualaceo. One of these was the combined arts of tailoring and “bordando”, or embroidering. Gualaceo, while not a major tourist attraction itself, was a necessary stop on the road to Chordeleg. Some of the items of the tourist trade were shirts and dresses heavily embroidered with flowery designs. On most afternoons while walking through Gualaceo’s streets, a glance through an open doorway would reveal women, singly or in groups, sitting at their embroidery frames and treadle or electric-powered Singer sewing machines, probably watching a soap opera on television. First they traced the pattern of the garment on a piece of blue or white cotton cloth. When it was decided what design was to be embroidered and where, the fabric was stretched on a rectangular frame set on legs at a comfortable working height above the floor. The embroiderer sat at the frame with her colorful balls of yarn before her and needle in hand, and quickly and accurately traced the design. Sometimes the yarn was looped both under and over the fabric, so that there was as much of the yarn under, or inside the garment, as there would be showing on the outside. Other times, short stitches were taken so that the bright embroidery was only visible on the outside, thus conserving materials. The embroidery was generally done by younger women in the town. Some took great pride in their own original designs and styles which they sometimes applied to bedspreads or tablecloths for personal use. When the embroidery was completed, the pattern was cut and rapidly sewn together on the machines. Piles of these garments could be found in clothing stores and souvenir shops in both Gualaceo and Chordeleg.

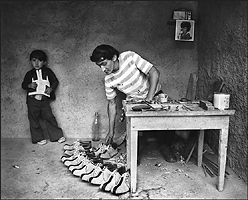

The major industry in Gualaceo and its environs was probably shoemaking. There was a vast domestic market for shoes in Cuenca, Guayaquil, and Quito. Shoe patterns from Italy or France in the latest styles were easily purchased and passed around among friends. While we were there, the platform shoe was the current vogue. The patterns were traced on strips of suede or leather, and cut out. These pieces were moistened and fastened to wooden forms of different foot sizes to shape and mold the leather as it dried. The cobblers glued some pieces together and sewed others. Some people did piece-work exclusively, using their home machines to sew the shoe’s uppers which were made of leather or synthetic materials. Any heavy-duty stitching required the specializedmachinery that was available at several shops throughout the town. The finishing work was again done at home.

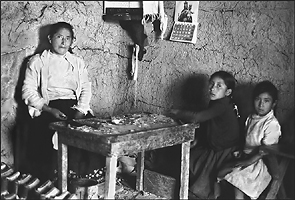

While some people were hasty in assembling their product, others were obviously highly-skilled craftspeople. One day we had been walking in the mountains near town and came upon a modest church that marked the small community of Santa Rosa. The church stood at the end of a short field, and there were several adobe buildings around the perimeter. At one of these we were able to purchase a couple of sodas from a barefooted Indian woman. Her two young daughters watched us silently from large brown eyes as we sat at a table and sipped our drinks. The room was very dark inside, with the only light coming from the open door. There was one other small table in the room, illuminated by the light from the door. The woman sat at the table and was putting the finishing touches on a half dozen pairs of very elegant, white spike-heeled shoes.

There were several minor industries in Gualaceo. A number of people imported the straw that was grown on the coast, and treated it in steaming vats to prepare it to be woven into hats. Bundles of this straw could often be seen fanned out on roadsides or in fields to be dried in the sun. The weavers purchased this raw material. When they were otherwise unoccupied, such as walking down the road or sitting in a collectivo, their busy fingers would skillfully bind the confusing mass of flying strands of straw into a wonderful head shade. They could weave different patterns, initials, or their names into the straw. Sometimes they used some straw dyed brown for a fine contrasting pattern with the usual ivory or white colored fiber.

Some people in town were skilled knitters who made the sweaters that were quite popular with the tourists. They used the wool that was hand-spun by the Indian women in the mountains whose sheep donated their coats. The thick yarn could be purchased in large skeins at the market on Sunday mornings from the women who gathered over by the gas station at the corner. Spinning the wool was as portable an activity as weaving hats, something to do while walking or riding about.

One of the most popular activities for persons with time to spare was to watch television. There were a number of soap operas from Mexico that were closely followed each afternoon. Soccer matches always attracted a large audience. On Sunday, crowds gathered in the doorways from which a television was visible, and it didn’t particularly matter what was on. Soccer and drinking were very popular sports among the men. Most Ecuadorian men are fanatics for a game of soccer or volleyball, although it may actually be the ball that is the true source of devotion. While waiting for the next game, they may be seen juggling the ball singly, or among themselves, with the object that the ball touch neither the hands nor the earth. When the men wanted to drink, the river and the cantinas were popular spots to go. A drunken brawl was a very rare occurrence. When the men got drunk together, they usually sang songs, weaving arm-in-arm down the street. Sometimes we were awakened out of a quiet sleep by a chord struck on a slightly out-of-tune guitar rising from the cobblestones below our balcony. Then we were treated to a romantic pasillo in three or four-part harmonies, rising in waves from the dark stone streets and gently lapping against the adobe walls as the comrades made their way home.

For the younger boys and men, the river offered a bathing place, and sport and meeting ground. Women were not encouraged to bath or swim in the river, so for them it was a place to wash clothes, or to walk and have a picnic. There was no laundromat in town, and if a woman had too many clothes to wash in her sink in the courtyard, there were Indian women who would take loads of laundry down to the riverside where they beat and scraped the dirt out on the rocks, and left the clothes to dry on the grass and draped over the shrubbery.

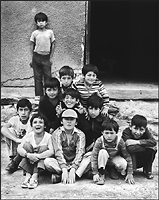

It was an unhurried life in Gualaceo. On most evenings, people strolled about the streets and parks, meeting and talking, and listening to music from phonographs or radios. Many nights the power failed, and the candles were brought out to create their shimmering pools of light in the darkness. Though there was work to be done, and dreams in the making, time was taken to enjoy and appreciate life amid the security of strong traditions and family ties.