Home Ecuador

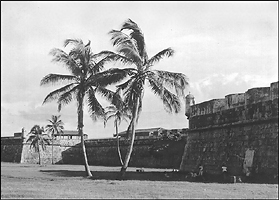

The sole paying passengers on the freighter Margaret Lykes, we had departed from New Orleans in mid-September, 1977, for a 2 week cruise to Guayaquil, Ecuador. Leaving the Mississippi behind, we sailed through the deep blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico and into the Caribbean, startled flying fish fluttering from our prow, heading for the Panama Canal. The Lykes made brief stops at the Colombian ports of Santa Marta and Cartagena for cargo exchanges before arriving at Cristobal, the Panamanian city on the east end of the canal. We transited the isthmus with the help of the locks and the rising and falling waters of the Caribbean , Gatun Lake, and the Pacific Ocean before emerging from Miraflores locks on the western end. We made a brief stop at Panama City before we began steaming down the western coast of South America.

The humid air of the Caribbean and Panama had been replaced by the cooler and drier air that formed its own currents above those of the waters of the Pacific. The lower air temperature that washed over us was the shadow of the great movement of water known as the Humboldt Current. The current is an upwelling of deep, cold, nutrient-rich water that nurtures the great sweeping schools of anchovy that provide a source of livelihood for a fleet of Peruvian fisherman and a much-needed item of export for the economy of Peru. However, the Humboldt is a fickle current, and in some years it takes a break from its cycle. The Peruvians call the Humboldt “El Niño” – The Child - and in those years that the Child does not appear, the anchovy never attain their vast numbers, with the resulting hardships for the economy and the fishermen. Most of the time, the cold water conspires with the ridge of rock known as the Andes to deprive the coastline from Chile to Northern Peru of rainfall, creating the great coastal desert with its minerals and monuments to both ancient and current civilizations.

We were twenty miles off the coast of northern Ecuador when we saw our first Ecuadorians. They were fishermen in long, narrow boats with a triangular sail on a single pole; tiny, fragile-looking figures in the vast blue water, seeking sustenance among the sea turtles, sharks, whales and dolphins. Our freighter slipped into the Gulf of Guayaquil late at night and, while we slept, a pilot guided us up the passage and parked us at a dock in the city of Guayaquil.

The immigration authorities were very hospitable and gave our passports a 15-day stamp. Later, in Cuenca, we found this would be sufficient to remain for 90 days. We chose an accommodation from our main source of information, a South American travel guide, and within minutes a taxi had deposited us amidst the stalls of sandal and tennis shoe vendors that flanked the entrance to the Hotel Santa Maria. Eight dollar/night bought us a thinly-walled room with two single beds and a view from the shuttered window over the busy street below. The street was filled with vendors, and their stalls with underwear, shoes, shirts and pants. After changing some travelers’ checks into the Ecuadorian sucre at a rate of about twenty-two sucres (“sucs”) to the dollar, we set out to wander the streets of the city.

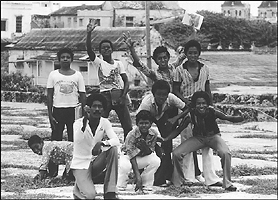

Like most cities, Guayaquil was noisy with the sound of traffic and construction. Unlike cities we were accustomed to, it was filled with an exuberant Latin spirit and ubiquitous peddlers of everything from chiclets to birds to wristwatches, and it rang with a language only basically decipherable to us. Growing up in California, we’d both been exposed to Spanish instruction in elementary school, but not had much opportunity to use it since. Despite recent attempts at learning Spanish grammar, much of the conversation we heard on our arrival in South America was indecipherable, at least to me. Peggy was way ahead of me on this.

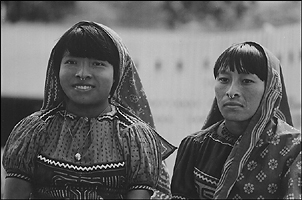

The weather was hot and humid in Guayaquil, and we necessarily spent a lot of time panting in the shade of the large trees found in the parks scattered throughout the city. We could obtain a similar feeling of relief while drinking beer in a sidewalk café, or the milky juice of a freshly cracked coconut sold by a street vendor. The museums of the city provided another opportunity to get out of the sun. While walking among the display cases and exhibits, we were reminded of ancient traditions and the varied cultures of the original inhabitants of the coast and mountains, each of them coming and going through time. We were told of the many different aboriginal cultures that were molded under the subjugation of Incan conquerors, and decimated by Spanish invaders 400 years ago. The weaving of these two traditions, the Indian and the Spanish, forms the fabric of Ecuadorian life today.

Our lack of facility in the Spanish language was especially confusing over the phone when one had nothing to interpret but an imperfectly perceived voice. We attempted several times to contact someone whom we’d met back in the United States, and who now lived in Guayaquil. These attempts were usually defeated by the combined force of the erratic telephone system and our limited linguistic abilities. Eventually we achieved our connection and we met and talked with Juan over some juice in a vegetarian restaurant. He assured us that it was possible to get “anything” in Ecuador, as long as one had the money and the connections. Just like at home. With limited quantities of the first and virtually none of the latter, we resigned ourselves to simply doing the most possible with what we had available.

A couple of days after our arrival in Guayaquil, we went to the airport to board a scheduled flight to the Andean city of Cuenca. Despite arriving at the airport early, we nearly missed the plane because we did not understand the garbled message from the loudspeaker announcing the departure. Leaving the humid coast behind we traveled by air into the mountains.

Cuenca is Ecuador’s third largest city after Quayaquil and the capital city of Quito. Spotted with parks and plazas and cut by several rivers, Cuenca’s narrow flagstone-paved streets are lined with buildings of stone and adobe. The streets were busy and crowded with people as we rode in a taxi from the nearby airport to a hotel. It was exciting to walk through Cuenca’s dusty streets. The contrasts were striking: the young people in their platform shoes, slacks, and wash-and-wear shirts, and the Indian women in flannel skirts, sweaters and straw “panama” hats; the businessmen in smart three-piece suits clutching briefcases, and the Indian men in sandals and dusty, baggy pants and worn shirts who transport merchandise about the city on their backs or on two-wheeled wooden carts.

There were several market squares in Cuenca which blossomed with country people and their wares every Thursday. One market contained the stalls of the dry goods, manufactured clothes and shoes, and the handicrafts of the weavers and leather workers. The Otavalo Indians from northern Ecuador were conspicuous by their aggressive salesmanship and never-ending supply of woven ponchos and chompas (sweaters). We began to recognize them solely by their call: “Poncho, mister?”

A small square beside a church nearby provided sales space for some jewelers, their wares pinned on boards propped against the old stone walls, and for the colorful, fragrant displays of the women selling cut flowers. A short distance down the street was a large park providing business opportunities to a squad of young boys with clothes stained in blacks and browns, and hands and faces to match. Unless one wears tennis shoes, it is impossible to sit on one of the park benches without being approached by several of these entrepreneurs with their beat-up wooden box in hand, intent on beautifying your footwear. And it is equally impossible to refuse them.

In the same park are the men who will immortalize tourists and locals alike with an “instant” portrait made on the spot, perhaps even hand-colored. The photographer shoots the picture with his ancient-looking box camera, not on a piece of film, but on a piece of photographic paper. He then thrusts his arms through some fabric sleeves into the camera’s interior and performs the ritual of development discreetly in the dark. The negative image on the paper that results is set on an arm in front of the camera’s lens, and re-shot in the same fashion to make the positive print. The entire process consumes about thirty minutes. We have the current upgrade of this process in our baggage – a Polaroid camera.

Walking through town, past the well-stocked stores and small restaurants, we arrived at the produce market occupying another town square. This is the largest sale in town and, though there are vendors who come every day, each Thursday the market floods into the adjoining streets with potatoes, cabbages, oranges, chirimoyas, naranjillas, cheeses, plantains, tomatoes, all the bounty of the countryside come to town. Accompanying this mass of edibles are the people who grow it, all the country folk who take the opportunity to renew acquaintances, pay old bills, and stock up anew. There are too many people with too much cargo on their backs or clutched in their hands to be contained on the narrow sidewalks, and they spill into the streets, narrowly missing speeding cars and noisy buses.

A bit further down the street is a small square dedicated to pottery, furniture, baskets, and utensils for the home and kitchen. Everywhere are the vendors of refreshments: fresh juices of tamarindo, naranjilla, or coconut; milk from a goat standing nearby; fried pieces of pastry, ice cream, and cookies. For more substantial sustenance, family chefs have outfitted spaces where hungry shoppers & sellers may buy a complete meal of tasty soup, rice, potatoes, plantain, beef, eggs, avocado, beets, tomato, lettuce, and carrots, prepared on the spot. What you see is what you get, which sometimes is a good argument for going somewhere else.

After a heavy rain in the afternoon, we went back out to the market under the long rays of the setting sun. Most of the market people had gone, but some of the chefs were busy over their cooking fires fixing soup in large pots. Others were barbecuing guinea pigs on a stick over a bed of glowing coals. The appeal of this Andean delicacy was not wasted on the starving Spanish conquerors, although well-fed North Americans might take pause at this rude treatment of the family pet. It was a local treat to buy one, marinated and brownly roasted, from a market vendor.

We checked the local paper for apartments for rent. After our humbling experience using the phone in Guayaquil, we thought that we could make a better impression, not to mention gather more information, by enlisting the aid of the hotel’s desk attendant in making our calls. However, it became clear that the price for accommodations in town were beyond what we wanted to pay.

The next morning we searched for, and eventually found, a collectivo (a van or bus) to transport us to Gualaceo, a small mountain town about 22 miles east of Cuenca. Gualaceo and the neighboring town of Chordeleg are famed for their craftspeople: shoemakers, weavers, jewelers, embroiderers, and potters. Our interest in handcrafts had brought us to this area, and we hoped to find somewhere to live nearby. The collectivo left Cuenca on a nicely paved road. After about twenty minutes, our van turned onto a graded road of dirt and rock, and bounced and rattled for another twenty minutes as we followed a river. This road eventually delivered us to the central square of Gualaceo. This large, concrete square, located next to the church, was bare this day but for several lonely meal stands and fruit vendors. A number of collectivos were parked at one end of the plaza. We walked across the street to a small and pleasant park. It had grassy areas, paths, benches, a central fountain surrounded by a low wall, colorful flowers, and shade trees on which someone had been practicing topiary. We found and inspected one residencial in town. We were offered two beds in a small room whose walls, which didn’t quite reach the ceiling, were lined with pictures of women. Somehow, it didn’t seem satisfactory for a long-term engagement.

The main streets of town were cobbled with stone, and we walked on one of these into the countryside. The buildings were nearly all built of adobe, the newer ones of a grey cement block. There was a lot of greenery, trees and cactuses growing out of the hillsides. We noticed cattle, pigs, and goats in the yards and fields, and farmers plowing with wooden plows behind teams of oxen. A small river, the Rio Gualaceo, flowed near town, and its grassy banks looked perfect for a picnic. Prospects for living quarters seemed slim, and this little town with its dusty streets seemed somewhat smelly and dirty, and slightly offensive to our American-bred sensitivities. We inquired in some shops about an apartment and the people were very friendly and helpful, advising us on prices, and escorting us to one they knew was vacant. Someone there advised us to come back in several days, as the owner was out of town.

A couple of days later, after having satisfied ourselves that living in Cuenca was too expensive, we returned to the apartment-for-rent in Gualaceo. We stood inside a courtyard and talked with the same woman we’d spoken with before. Now we gathered that the owner would not return for another two weeks, but the lady suggested we go across the street. Someone there directed us to try another location further down the cobbled road. This one turned out to be occupied, but after some ill-comprehended banter with two women, we were motioned across the street once more. We entered a building and went up a flight of stairs. A woman who lived there said that there was an unoccupied apartment upstairs. We kept asking her where the owner was, but we couldn’t understand her reply. She finally became exasperated and made us go to the window over her balcony from where she pointed out the entrance to the building next door. That worked for us. We went back downstairs and into the small shop that occupied the next building. The old woman we encountered there was the dueña, the owner of the vacant apartment. She sent us back upstairs in the company of a young man who would show us around. The man opened some doors on the third floor to show us a bare room with wooden floors. Directly across the room were some large windows that opened onto a narrow balcony overlooking the street. Going upstairs, we were introduced to the cocina, or kitchen. This was a concrete-floored space open to the weather on three sides above the waist high walls. From under the tin roof there was a fine view over the town to the river and the mountains rising beyond. In one corner was a sink. While we were marveling at this unusual kitchen, the dueño appeared, the husband of the old woman downstairs. He was carrying a set of keys, and he opened the doors that led into two rooms behind the kitchen, and showed us another small room downstairs. There was a brick-paved patio on the third level and a toilet and sink. The rent was 600 sucs/month, about $27. We accepted immediately and agreed to move in the following day. Then we said good-bye to the young man who had shown us the space, Leonardo Cárdenas, and our new landlord, Señor Piña.

It was a very pleasant day, so we followed a road out of town that took us over the old wooden bridge that spanned the river and on to the town of Chordeleg. As we walked, we marveled at the country. The altitude was approximately 5500 feet above sea level, and the land was modeled into a series of hills and valleys with the river below us and water gurgling through irrigation ditches in the fields that bordered the dirt road. Century plants poked their thorns skyward all across the hillsides, interspersed with tall grasses and stands of eucalyptus. Pigs, sheep, cows, chickens, and some turkeys were scattered around the fields and adobe-walled houses. The air was fresh and clear, and the flowing clouds in a rich blue sky played their shadows across the mountains. This area had long been a home to men, and the steep hillsides, though difficult to walk on, often had rows of corn planted on them. Here and there among the brown homes and cultivated fields was an occasional church, its white walls reflecting the light of the sun like a beacon.

The town of Chordeleg has its own impressive church, and we sat on some steps nearby and refreshed ourselves with a warm beer. Chordeleg is a small town, and tourists flock to its many shops filled with jewelry, pottery, knitted sweaters, embroidered shirts and dresses, hats, and carved wood. We walked back to Gualaceo, oblivious to the fact that the occasional small truck that passed us was the local transportation system. However, the road was mostly downhill now, and we refreshed ourselves with an orange on the banks of the river while listening to the women slapping clothes on the river rocks. A cool fruit drink in the plaza prepared us for the dusty ride back to Cuenca.