Home Ecuador

We hitched a ride to Cañar with Vicente, a man who owned one of the grocery stores in Gualaceo. He was driving his big Mercedes Benz truck on one of his regular trips to Guayaquil to buy merchandise. We squeezed uncomfortably onto the front seat with he and his wife for the 1.5 hour ride over the heaving road to Cañar. Vicente inquired whether or not we had a gun. He said that there were cut-throat thieves at Tambo Viejo, a settlement on one of the roads that led to Ingapirca, thieves who preyed upon the tourists on their way to the ruins. However, Tambo Viejo could be avoided, along with its bad reputation, by taking the road through Tambo, a little further down the highway.

Vicente let us off on the outskirts of Cañar, and we walked up a steep, cobblestoned street into the center of town. Cañar was a little larger that Gualaceo, and built on rolling hills. The area was known for its dismal weather, and did not disappoint us. Low gray clouds blown about by a cold wind leaked a sporadic drizzly rain over the old adobe buildings of the town. It was a picturesque town with its climbing and curved streets. When an old building fell down, the site was rebuilt with more modern design and materials, but most of the adobes still endured.

We were wandering about the streets in search of lodging when someone came by in a small pick-up truck and asked if we were headed for Ingapirca. We weren’t at that moment, but were reassured that it didn’t seem difficult to reach the ruins. We were directed to one pension, but it looked like an abandoned building. We eventually induced a lady to leave her store and escort us to a place to stay. We were having difficulties because there were no signs out front to identify accommodations, but we finally were able to rent a room for the night. We’d seen a single restaurant in our wandering, and returned to it now for a hot lunch.

Our next task was to search for transport to Ingapirca. Near the town square was a taxi stand, so we stood there in anticipation. We’d been waiting about fifteen minutes when a man came up to inform us that there were no taxis anymore. He also mentioned that it was easier to find a ride on a Sunday when there were more tourists. He suggested that we might find a private car to take us for about 15 sucs. We looked around some more and were eventually directed to a certain street corner where a truck bound for Ingapirca was rumored to pass. While waiting, we began conversing with three young men, and they offered to show us where the car originated. They’d been listening to some pop music on the juke box, and they were curious about who or what “Daddy Cool” was. We thold them that it could be translated literally to “Papa Frio”, however “papa” also means potato. “Cold Potato” didn’t quite transmit the intended nuance.

We walked downhill towards the town square, and one of the men, by calling and whistling, managed to flag down the truck as it sped by. We spent the next half hour driving around town as the owner picked up cargo and passengers. Our last stop was the small town of Tambo. The driver had the same opinion of the people of Tambo Viejo as had Vicente – “male gente”. The unpaved road leaving Tambo climbed steeply and gave a fine view of the country of the Cañaris, the Indians who populated this area. The mountain ridges were colored in drab grays and browns, with some green marking the comparatively few cultivated areas. There were not many trees. The land sloped in long plateaus, cut by deep furrows which plunged down to a river, the Cañari, flowing among the stones in the lowest reaches. Where there was vegetation, the eucalyptus and penco cactus stood out as the prominent inhabitants. The Cañaris, in common with other native populations, distinguished themselves with their own peculiar mode of costume. The men wore thick wool pants, shirts and ponchos; the women were clothed in long skirts, blouses, capes, and necklaces. Both sexes wore the same grayish-white felt hat. We saw them often in their fields, or herding sheep or cattle along the road.

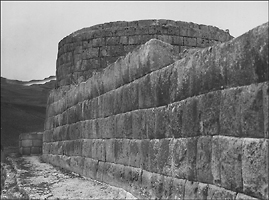

When we arrived in the small village of Ingapirca, the driver sent his ayudante to us to collect the fare, 20 sucs. The ruins were perched on a hill a short distance away, and we walked there through the drizzle and mists. The stone walls that remain supposedly are part of what once served the Incas as a temple, and living and storage quarters. The location afforded a fine view over the desolate mountain country. The quality of the stonework varied, and so did the general color of the stone and its attendant algaes and fungus. The main temple structure was built with large rectangular blocks of stone fitted closely together with the skill that Inca masons are celebrated for. The low walls marking the rooms were built with irregularly shaped rocks between which the mortar of mud was plainly visible. It gave the impression of having been restored in a way inferior to its original construction. As we walked through a stone doorway, two Indian men were standing by the ruined wall, one with a shovel in his hand. At our appearance, they turned and walked away, leaving the mysteries of massive stone in their wake. Inside one of the rooms, the walls were inset with niches at about five feet above the ground. Their original use might have been as built-in storage areas.

The temple was oval-shaped with the remains of two rooms located atop it. We couldn’t find any means of entrance to the main edifice. The walls of the temple were generally a slightly greenish, or bluish color, while the walls of the adjoing quarters were more reddish and yellowish. One side of the hill sloping away from the temple was terraced in the classic Inca style with rock reinforcing walls. From a hill nearby, the temple made a vivid and impressive view, the regular and massive, but light-colored stonework looked like a timeless sentinel as it perched on the crown of its hill, the gray skies lying over it and the winds blowing mist and scattered clumps of cold rain along its face.

On this same hill were the “Incas’ Baths”, holes and channels cut into the solid rock. We talked to a man there who was a part-time caretaker for the ruins. He occasionally visited the area of Gualaceo, for he had a relative attending school in Chordeleg. He couldn’t tell us much about the history of the ruins, but he identified a well-built, freshly white-washed adobe building nearby as being owned by the Ecuadorian Banco Central, and for the use of visiting archaeologists and anthropologists.

In another area were what remained of the walls of another compound, regularly laid out and symmetrical about a line running lengthwise down the center of the building. In what might have been a courtyard was a large stone protruding from the ground. In front of this was a circle of stones filled in with more stone all set firmly in the earth. On one end of these ruins was a series of round stone-lined holes in the ground that appeared to be connected by channels. This set of ruins was called “Pilaloma”. In between the two main ruins there was a large number of stones from the walls that had been gathered into rows along the ground, many of them with round holes drilled in them.

To the masons of the Incas, the stone that was such a vital element of the mountains in which they dwelled was a source of strength and durability to be molded to human uses. Through their skills and labor, the earth itself was mated with human aspirations to create the child Ingapirca, still impressive in its old age.

We discovered that there were accommodations to be had in the village of Ingapirca, however we’d already made arrangements to stay in Cañar. When we were ready to return, we found the ayudante of the truck that had brought us hanging around nearby. He and the driver said sure, they could take us back, but it would be a special trip for them since they claimed to have no pressing business to conduct in Cañar. So although the ride up had only cost 20 sucs, if we wanted to return the price was 150 sucs. These men were obviously more sophisticated than their counterparts at Tambo Viejo.