Home Ecuador

When I entered, the owner was on his knees in the corner before a large mortar. He was using a stone to grind bits of sulphur (he showed me a yellow chunk) with water into a yellow paste. The perspiration rolled down from his forehead into the heat of the afternoon as he alternately pushed the large stone around and scraped the residue from the sides of the mortar. This process consumed a couple of hours of grinding before the last bit of sulphur had finally surrendered itself to the paste. The next step was to add a cup of a thick, brown syrup that he said was made from a plant that grew near the coast. He mixed this last ingredient into the paste by hand until he had a thick liquid, somehow white in color.

Earlier the man had washed and cleaned the straw hats and set them outside on the cobblestones to dry in the sun. The shape and proper headsize were maintained by inserting a wooden block into the space where a head normally resided. Now he brought the hats inside and, one by one, applied the white syrup to them with a brush. He coated them inside and out, and again set them aside to dry.

In the meantime, the man brought out his old iron. It was a type of iron that would be considered antique in the United States, but was still a common piece of equipment in every hat shop. The man lifted the top of the iron in order to determine the condition of the chunks of charcoal inside, and then attached a bellows to a small hole at the rear. As he pumped the bellows, sparks and ash flew from the exhaust funnel at the front, looking like a miniature steam boat about to depart for the other side of the counter. When the iron was properly heated, the man selected a hat and placed a cloth over the area to be worked. As he pressed each hat, he smoothed and flattened the straw that had swollen from its previous washing, and set the coating of white paste that would act as a stiffener, whitener, and somewhat as a waterproofer. This last is qualified, for Peggy had bought a new hat that hade been coated with such a paste. As we returned home that day we were caught in a rainstorm, and the water rolled off the hat in small white rivulets down her back.

We lived on the third and fourth floor of a small building in Gualaceo. As this was one of the tallest buildings in town, we enjoyed a fine view of the mountains that looked down on our small valley and its attendant river. On the other hand, we were victimized by the low-pressure water system that often left us waterless during daylight hours. We were occasionally forced to avoid the area of our third floor outhouse.

On one of these low-pressure days, I ventured forth to seek the services of a barber, for I was in need of a shave. I went to several shops, but either no one was available, or they were busy. Then I remembered one shop located in a building across from the park. As I looked in the doorway, a man sitting in a chair reached out to take my hand and draw me inside. He was a little unkempt, and his eyes rolled slightly in their sockets. He gestured at a shelf upon which was displayed a radio-tape player. It had a “se vende” sign on it. I said it was nice, but I wasn’t really in the market. I realized that he was drunk, and noticed another man snoozing in one of the shop chairs nearby. The barber didn’t seem particularly friendly, but he still had his clammy hand clasped to mine, so I accepted the seat he offered. I determined not to get a shave there. It was nearly impossible to understand him between his castellano and slurred speech. On a table across the room were the instruments of the debauch: bottles of Zhumir, 7-Up and Pepsi.

The barber began gesturing at his feet. I’d already noticed, from seeing him about town, that he walked strangely, and now I saw that his feet were disfigured. He referred to a letter in explanation, and eventually commanded enough energy to rise from his chair and pass behind a partition. It occurred to me that this was the perfect opportunity to slip away, but that seemed a little cowardly and rude. Besides, I was curious about whatever it was he wanted to show me. He returned with a large manila envelope which he thrust in my hands. His name was on the outside, along with that of a doctor. The date was 1964. He opened the envelope and withdrew some x-rays which he recommended that I study. About this time, the other man was rousing from his stupor. He propped himself on one arm, blew his nose on the floor, and managed to look in my direction. Then he asked a couple of times “You speak English?”, using what I was sure was his stock English phrase. I had my hand back, so I smiled and said “Hasta luego”, and walked out the door.

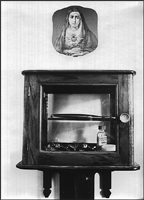

On another day of our intermittent water shortage, I again searched out a barber. I favored one that I often passed on my way to Gualaceo’s post office. It was a cool, dim shop with one old chair facing a mirror on the wall. The owner walked out from the back of the shop, eyeing me with amusement and curiosity. He needed a shave himself. I explained to him the circumstances which had compelled me to enter his shop, and he was solicitous while suggesting that I might store some water for just such an emergency.

He invited me to occupy the chair, and spent the next several minutes whipping up a lather in his cup and thoroughly soaping my budding beard. Then he pulled out his blade, an old veteran of a tool that he had to resurrect by stropping it vigorously on the strap that hung from the side of the chair. He flicked it on his fingers, making it ring while testing its sharpness. Having satisfied himself of the keenness of the edge, he began to scrape at my face, rather carelessly I was inclined to believe. Although I seldom have myself shaved, my anxiety was not unfamiliar, for I am no stranger to the dentist’s chair. Every occupation has its “tricks of the trade”, those cunning short-cuts and techniques that facilitate getting the job done, and I believe this man used several to create some particularly hair-raising moments, that being his goal. However, my barber was a thorough man and after disposing of the first soaping, he felt inclined to apply another. After this second had been removed, he still wasn’t satisfied and, rubbing my face with his hand, he detected further possibilities. He exploited these by scraping without the hindrance of any soap whatsoever, until he’d driven what was left of every hair on my face into its puny follicle.

At this point, the craftsman stood back a bit and took aim with his atomizer, enveloping my face in a misty cloud of cologne. He used the towel around my neck to wipe my cheeks, but left it to me to dab at my eyes. Next he took up a feathery white puff from the table and dipped it into a box of powder, and padded that on my face to fill the holes. He picked up his scissors then and, though I was prepared to stop him should he start snipping at my hair, his innocent intent was to trim my sideburns. Finishing this, he allowed me to dismount from the chair, and I did so obligingly. As I stepped from the shop into the morning sun, I felt it was bargain at only .20 and a sore, but nevertheless intact, face.