Home Ecuador

The procession in Gualaceo took place on the day before Christmas. It was similar to, but grander than, the one that had marched through Chordeleg a couple of days previously. We had been invited to visit the panadería on the day of the procession in Gualaceo. When we arrived, we were given glasses of colada that had been prepared especially for Navidad. It was a drink composed of just about every fruit that was available at that time of year: piña, papaya, mango, banana, babaco, or, as they told us, “todas las frutas”. The fruit was all mashed together and thickened with maicena, or corn starch. The maicena probably could have been bought in a store, but Rosa and her family had started making their own several weeks previously, extracting the hearts from hundreds of corn kernels. The colada that resulted was sweet and chunky, so thick that it might have been chewed. The folks at the panadería had placed a big bowl of this refreshment in their store, and many people came in from the street to share it.

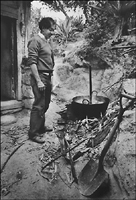

Near the baking oven was the room that served as the kitchen. They also had another kitchen with a new gas-powered stove, but some things were better done in the old ways. The walls and cooking pots in the old kitchen were a sooty black from the smoke of the wood-fueled cook fires. Several chickens, their blood still fresh on the dirt floor, were boiling in a ceramic vessel amidst the coals. A fan of woven reeds was waved to urge the embers to glow more fiercely.

Outside, the participants were assembling for the procession. We were urged to watch from the windows on the second story, but we preferred to be outside on the street, closer to the action. We were given a couple of chairs and settled on the narrow sidewalk, while up and down the street spectators were gathering in windows and doorways, and on balconies. Pretty soon we could hear some music in the distance, and it wasn’t long before an army brass band, on loan for the occasion, came marching around a bend and down the cobblestones toward us. Following the band was a small mob of people, some in costumes and others dancing about. They were being accompanied by a more traditional ensemble, a man playing accordion, another rapping on a snare drum, and a third beating a bass drum. A little girl supported the group with the accordion’s box in a sling on her back.

After the dancers had passed there rode several mounted figures. They were young boys with thick beards stuck on their faces, and wearing strange-looking hats or crowns. Their costumes were in reds and golds, blues and yellows, and they definitely seemed to represent kings or wise men. Walking behind the horses were some young children, the youngest holding the hands of their parents. Some were wearing the traditional Indian garb and carrying bundles of sticks or food on their backs. The boys had been smeared with burn-cork beards, sideburns and mustaches. The girls had red rouge on their cheeks. Some of the girls looked like little Spanish princesses with long satin dresses and shawls, and were adorned with “jewels”.

The younger children were followed by a line of “floats”. There were about twenty in all, automobiles that had been rigged with platforms upon which scenes from the Bible had been recreated, complete with props and children dressed for the parts. Each was identified with a small sign, such as “Adam and Eve in Paradise”, “The Birth”, “The Annunciation”, or “The home of San Joaquin”. Behind the last float was a line of teenaged men and women in costume. They were dancing in unison to the music provided by a dump truck at the end of the procession, a speaker mounted on its grill. In between the truck and the dancers was a group of well-dressed, and very solemn-looking men and women. Several were supporting the posts of a golden canopy, under which walked an elderly woman in spectacles carrying a carved wooden statue of the baby Jesus in her arms. The grand finale was the lumbering dump truck and, although doing nothing more than blaring music, an impressive presence as it rumbled down the narrow cobbled street.

We retired to the bakery, and were escorted upstairs to the large living room. Along with Rosa’s immediate family was the family of her daughter, and that of some close friends. We occupied the chairs that lined the walls and talked. Two of the men had spent time working in New York, one of them as a chef for seven years. They enjoyed practicing their English on us, and we our Spanish on them. The men left after a while, and when they returned, they carried gifts for the children. These consisted of a cellophane bag containing cookies, bonbons, and toys. For the boys there were balls and a plastic racing car; for the girls, a miniature set of nesting metal pots.

As we talked, Rosa’s husband Pancho roamed the room with a small plastic tray upon which sat several small glasses, a bottle of Zhumir, and one of 7-Up. He would pour some of each into the glasses, and when he would offer a glass to us, we’d smile and say “Salud!”, and toss it down our throats, returning the glass to the tray for the next round. Then we’d grimace, or cough, and feel definitely warmer inside. After a few passes, we felt it was about time for us to leave. However, Rosa and Christina talked us into staying for dinner.

In the kitchen now was a large bowl of potatoes in a sauce, and nearby was a pot of hairless guinea pigs. Móte was boiling in another. The smoke of the fires wafted through the room, and its spicy odor combined with that of the food to set stomachs rumbling. Christina gave us a preview, a tasty piece of chicken liver. I noticed that the blood I’d seen earlier had been lost in the dust. The rest of the chickens, seemingly unconcerned by the fate of their comrades, continued scratching in the yard, and several pigs grunted in their small pen. As the afternoon wore on, the women worked on the food, and the Zhumir worked on our heads.

Eventually the table was set, and we were all seated. The first course was a soup of thick, buttery chicken broth, with large pieces of meat in it that we ate with our fingers. On the table was a platter of pickled vegetables and beans. I selected an innocent-looking green pepper. I presume the Zhumir must have fogged my senses, because I am seldom foolhardy enough to consume a pepper in a single mouthful. A raging fire welled up in my throat, searing my tongue and lips, and driving tears from my eyes. I didn’t want to say anything, posing instead as the veteran pepper eater. I took a long time to finish the soup, because every sip fanned the flames in my mouth.

The second course was served, and one of the men signaled us to begin, “Vamos a!”. The food consisted of a heap of rice with a piece of chicken sitting on top, some lentils, onions, and egg. Two courses was enough for me, for I was under the compulsion, learned long ago, of cleaning my plate. The others were accustomed to leaving a lot of their food uneaten, but it was not wasted as it went to fatten the pigs. The last course was a plate of potatoes and a bit of guinea pig. We were all thoroughly satisfied. The dinner was topped off by a shot of Zhumir to “settle the meal”.

We went back upstairs for a while before departing for a walk around the park and plaza. There were many people strolling through the dark streets, and music drifted into the air from buildings all along the way. The church service was ending and a crowd of people walked out the wooden doors into the night. A full moon was shining on scattered clouds, and the glare of its light blocked out all but the most persistent stars.

Leonardo Cárdenas, one of the first people we had met in Gualaceo, had invited us to his parents’ house for Christmas dinner. Leonardo and his father were woodworkers and carpenters. Leonardo rented a small shop across the street from where we lived. The bread-and-butter of his business was turning out lathed pieces of wood to be used as legs for tables and chairs. His shop floor was usually covered with several inches of wood chips, while he stood behind the spinning lathe in a shower of shavings that leaped from his gouge. Leonardo was a well-built man and proud of his strength. He enjoyed working out with weights, and was impressed by the photos of body builders that he’d seen in some magazines. He was friendly and outgoing, and enjoyed telling us jokes and stories, most of which were too elaborate for us to understand. He and his wife, Claudia, lived in a rented building off a field near the end of town.

Christmas fell on a Sunday, and it was market day as usual in Gualaceo. We finished our shopping in the morning, and at about noon we set out with Leonardo and his younger brother, Augustine, for their parents’ house. They lived at the top of a hill that looked out over Gualaceo’s valley. There was a church perched there that was a familiar element of the view from the kitchen of our apartment. The area was known as “Cafshan”.

We crossed the wooden bridge over the Rio Gualaceo, and immediately embarked on a steep, rocky path up the hill. We were met part way by Sr. and Sra. Cárdenas, and another brother, Eugenio. Leonardo’s father was short and thin, but wiry. Sra. Cárdenas was stockily built, and they were all in fine physical condition from the almost daily regimen of walking to and from Gualaceo, and working in the fields. When we had reached the church, we paused for a moment to admire the view, and then continued across the hill until stopped by some barking dogs. Sr. Cárdenas went ahead to clear the way, and we approached the poncho-draped figure of Leonardo’s grandfather, who also had a house there. We all shook hands, and it was only a few more steps to the adobe-brick buildings that comprised the home of the Cárdenas’. One building was the kitchen, and the other was divided into several rooms used for living and sleeping. There was a mud wall that formed a protected area in front of the living quarters. This patio had been swept clean and furnished with benches and chairs.

Sr. Cárdenas pulled out an old steel-string guitar, blew the dust off, and played a few tunes. Leonardo was a talented musician with a broad knowledge of Ecuadorian music. He could also play a melodious “saxophone” on the leaf of a nearby cherry tree that he cupped in his hands. We attempted the same trick, but never got beyond a farting sound. Glasses of Ecuadorian wine were passed around, a sweet-tasting muscatel served from the ubiquitous plastic tray, but in glasses “Made in France”.

Peggy went to help in the kitchen, and I was taken on a tour of the property by Sr. Cárdenas. Their farm was located on the rim of the hill, and there was no irrigation other than what fell from the sky. December had been unusually hot and dry there, and the corn was small and a little ragged-looking. A good rain in January might save it. From there we could look down the hill a short distance to where the land leveled and began curving up again. The corn growing there benefited from run-off from both sides, and was obviously doing much better. There was also a patch of ground that hadn’t been used for a while, that Sr. Cárdenas characterized as “fresh”, but this year had been planted to corn. This crop was plainly taller and greener. Several types of trees, cherry and peach, provided their fruit to the family. Among the corn stalks were bean plants and squash. A few pigs were tied up and grunting in the shade of thatched shelters in the fields. Some were destined to be eaten by the family on special occasions, and the others sold. The fields were fairly rocky and difficult to plow. The larger stones had been gathered together in large piles. The boundary lines of the property were marked by the thick and thorned, gray-green leaves of the penco cactus.

As soon as we’d returned, I was taken on another tour by the youngest son, Augustine. He took me directly to the peach and cherry trees where he filled my pockets and hands with the fruit. The small peaches, though green, were sweet. We went back to the house where they had started to drink chicha, a fermented beverage of maiz and a fruit, chonta. Sra. Cárdenas had made it in earthenware jugs. The chicha tasted tangy and refreshing, but not alcoholic enough to be noticeable. Bits of ground maiz settled at the bottom of the glass. Sra. Cárdenas was dressed “Indian style” in a red wool skirt, blouse, sweater, her black hair in two braids, and a white straw hat on top. She was working in the small building that served as the kitchen, its inner walls black from accumulated soot. A wood fire burned in the corner, and the ceramic pots were supported in the flames by stones. Eugenio was sitting on a short stool and barbecuing guinea pigs on a stick. In another corner of the kitchen was a small herd of live guinea pigs which were the happy recipients of the potato peelings. They were tunneling through the mound of grass and straw in their pen, and standing “head-out” in the niches in the walls. They played tug-of-war over the peels and cried in their high-pitched voices, the sound which inspired their Ecuadorian name, “cui”. On a table was a small, gas-burning “camp” stove. Claudia and Leonardo’s sister were also in the kitchen, peeling potatoes and hard-boiled eggs.

A table was placed in the space between the buildings, and dinner was opened with a round of muscatel. Most of the men, and Peggy, were seated at the table outside. The rest of the women and the grandfather were eating in the kitchen. The first course was soup, a chicken broth with bits of hard-boiled egg and onion in it. A glass of chicha was poured to accompany the meal. The second course consisted of potatoes with portions of barbecued cui on top. The guinea pig was salty, rich, and greasy, and there were no napkins. We licked our fingers, and threw the bones to the dogs gathered expectantly under the table and benches. We were pretty full by the time the final course was set before us. It consisted of large, gray beans with slices of tomato, and a portion of turkey. The meal was topped with another glass of wine. We all thought it a big joke that Peggy couldn’t eat the guinea pig’s head, but I had to refuse it, too, when offered. We washed our hands in a small bowl of water, and then posed for pictures with the Polaroid camera we’d brought along. We ended our visit with a final round of wine and chicha, and were invited back by the Cárdenas’ in February for Carnival.

As a counterpoint to the festivities of Christmas, to remind us of our mortality, there was an accident involving a bus overloaded with Indians and country folk on their way to the market. The vehicle went over one of the precipices characteristic of Ecuadorian roads and took the lives of 37 people. For the next several days, the church bells rang in mourning as groups of black-clothed friends and relatives carried the caskets through the dusty street to the cemetery.

As New Year’s day approached, the stores in town began to display masks along with their usual commodities. These masks, in the likenesses of traditional and imaginary characters and current political and social figures, were used as part of the New Year and coming Carnival celebrations. Clusters of neighbors pooled resources to erect small stages on the street corners. On these stages were assembled scenarios mimicking the courts, television shows, politicians, and current events that represented the waning year. These sets were peopled by “clowns”, or dummies fashioned from old clothes and stuffed with straw, sawdust, and rags, with masks from the stores for faces. On New Year’s Eve we went for a ride with a neighbor, and joined a parade of vehicles and people on foot that was touring these three-dimensional cartoons. Through the streets passed groups of young people in masks, dancing to the music that was being broadcast from the scenes, and from the homes and shops along the way. Old people stood in the doorways, or on balconies, calling out “Baile!” and laughing as the groups in the street spun and clapped. As midnight approached, the straw dummies were thrown into piles in the street, and the old year went out in a pyre of flames and smoke. People in the crowd added some tokens of the year’s memories to the blaze, and they inaugurated the New Year with a round of drinking and dancing at parties around town.